THE

ETERNAL VERITIES

For Old Souls In Young Bodies;

"Let each child's mind be as a pleasant inn where gentle thoughts of service may enter and abide."

DEDICATION

To the beloved Teacher and Friendly Philosopher, Robert Crosbie, who taught what H. P. Blavatsky and William Q. Judge had taught before him — pure and simple — who changed it not, nor added, nor subtracted from it; but who imbued it with his life, made living Their Example. What is in this book is what was learned from him. It is dedicated to him, and to all — young or old — who seek the Truth, that they may help as he did.

Contents

- PREFACEv

- I. THE PATH1

- THE FIRST TRUTH

- II. TRUTH13

- III. LIFE24

- IV. SPACE36

- V. GOD46

- THE SECOND TRUTH

- VI. LAW54

- VII. KARMA65

- VIII. MORAL CYCLES76

- IX. DHARMA86

- X. CYCLES96

- XI. ETHICS107

- XII. REINCARNATION141

- XIII. SOUL154

- THE THIRD TRUTH

- XIV. BEING178

- XV. THE LADDER OF BEING185

- XVI. EVOLUTION IN ANALOGIES193

- XVII. THE ELDER BROTHERS200

- THEOSOPHY SCHOOL SONGS

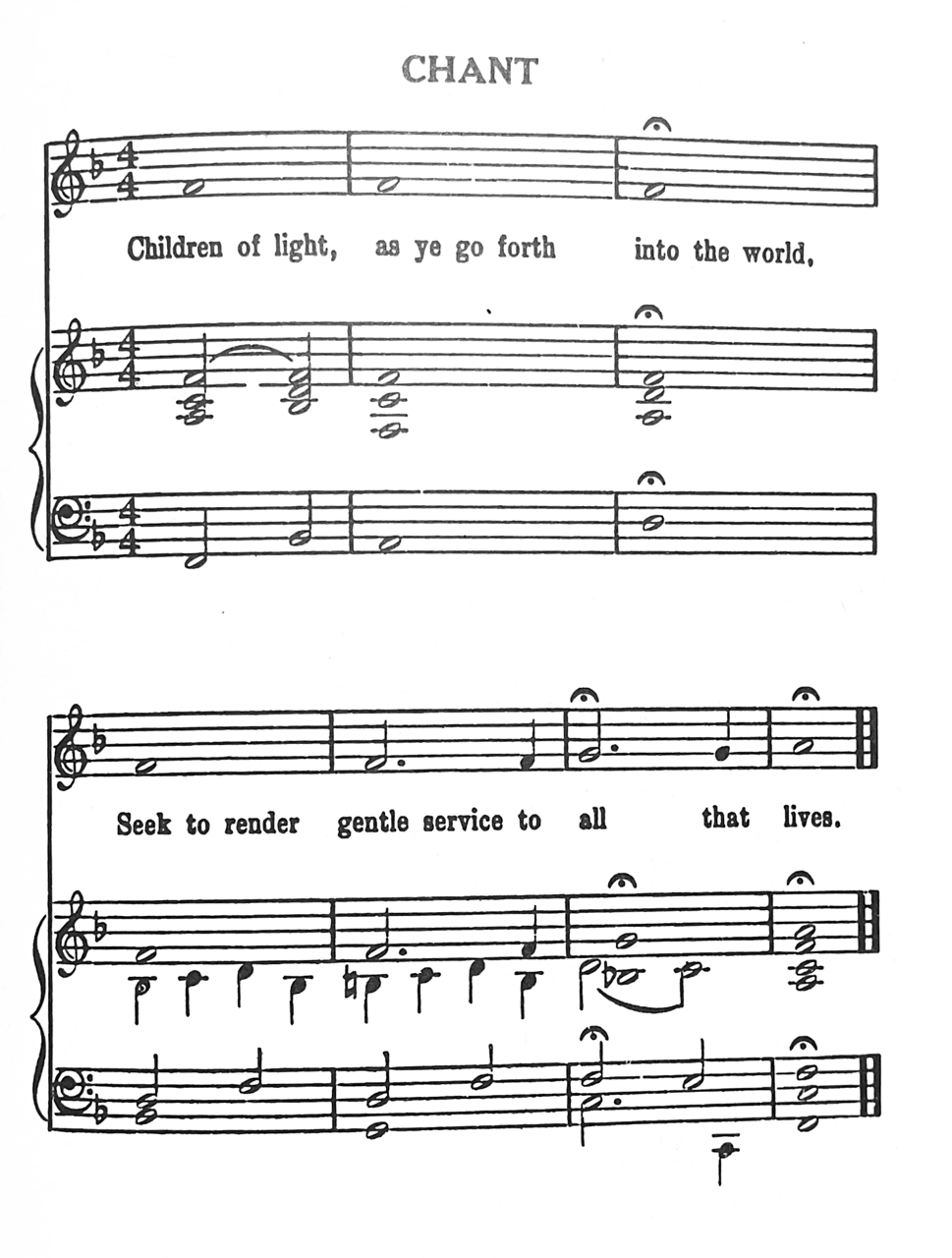

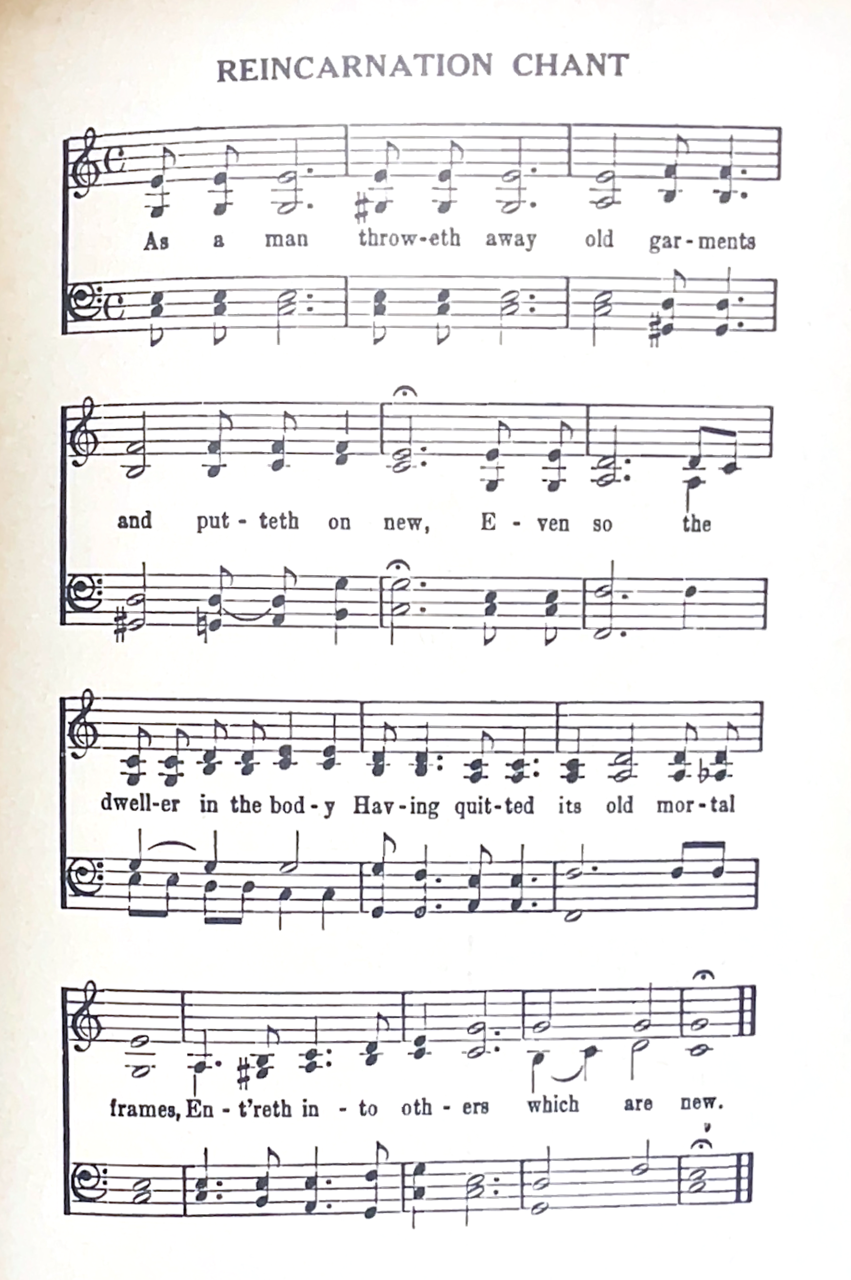

- CHANT217

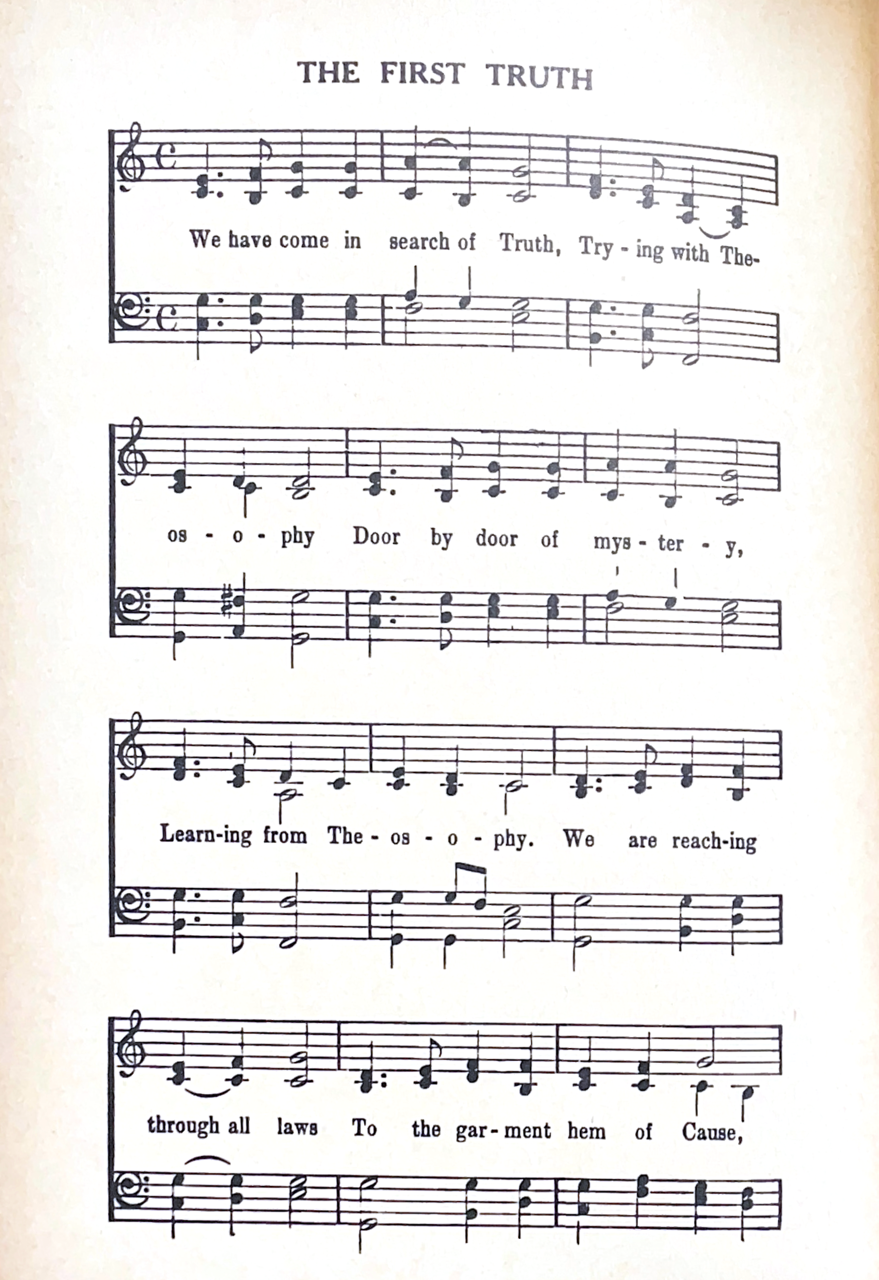

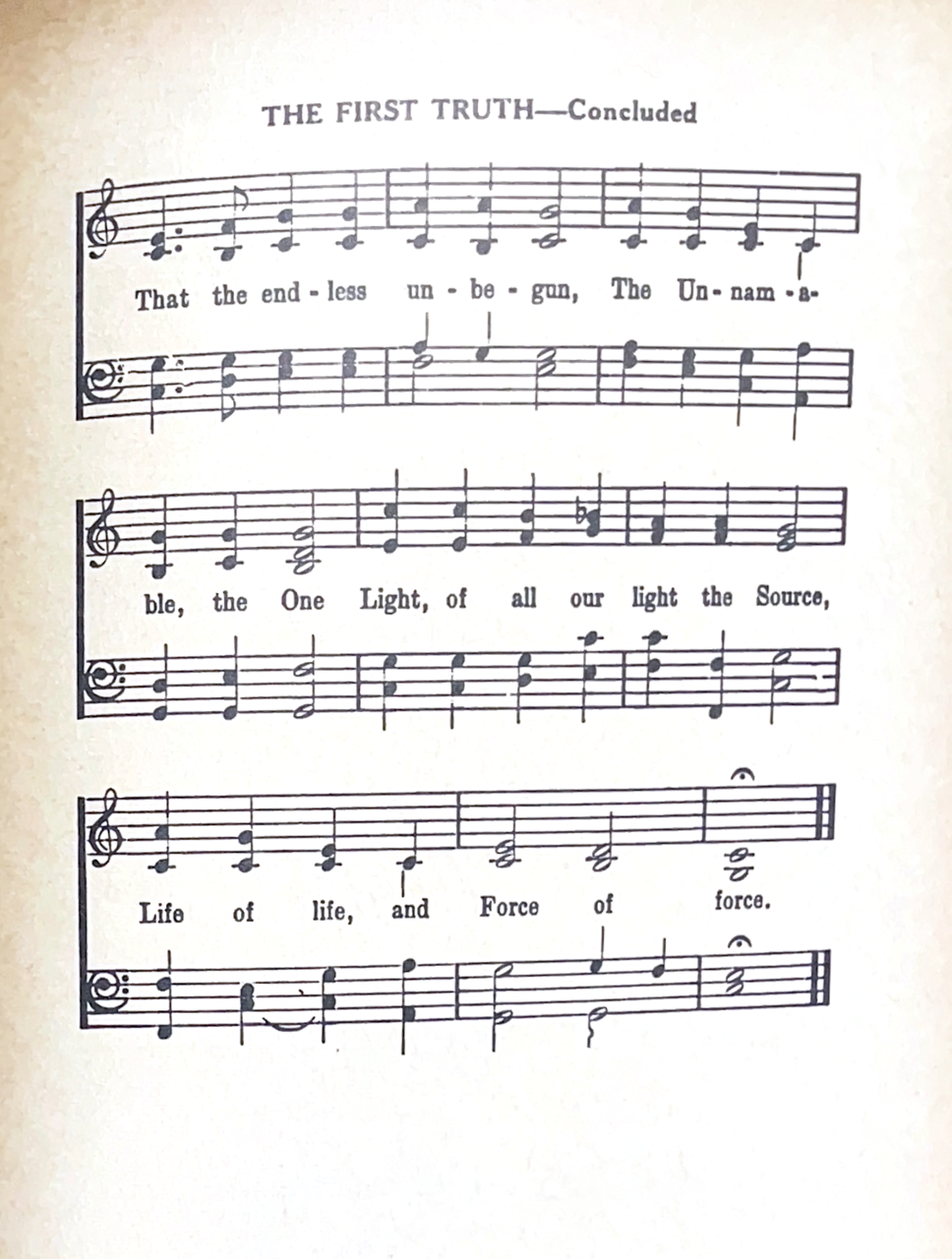

- FIRST TRUTH218

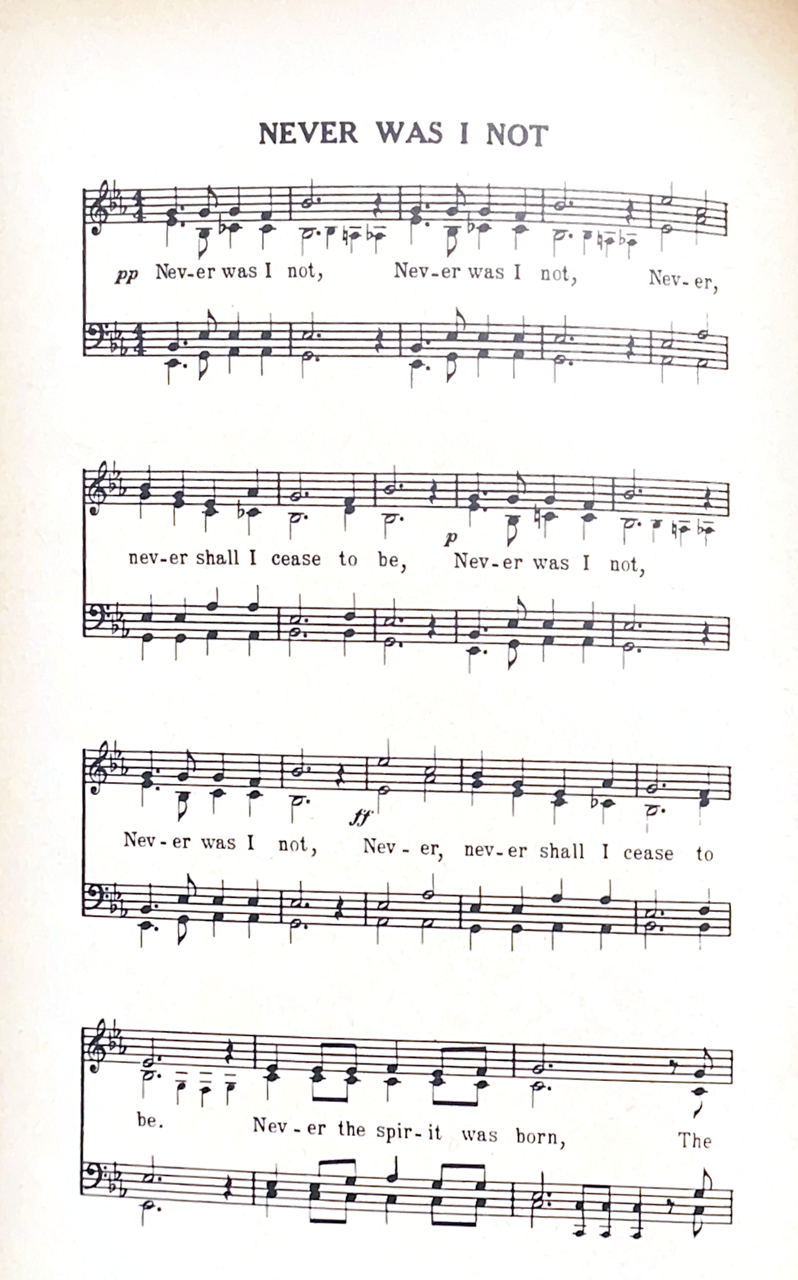

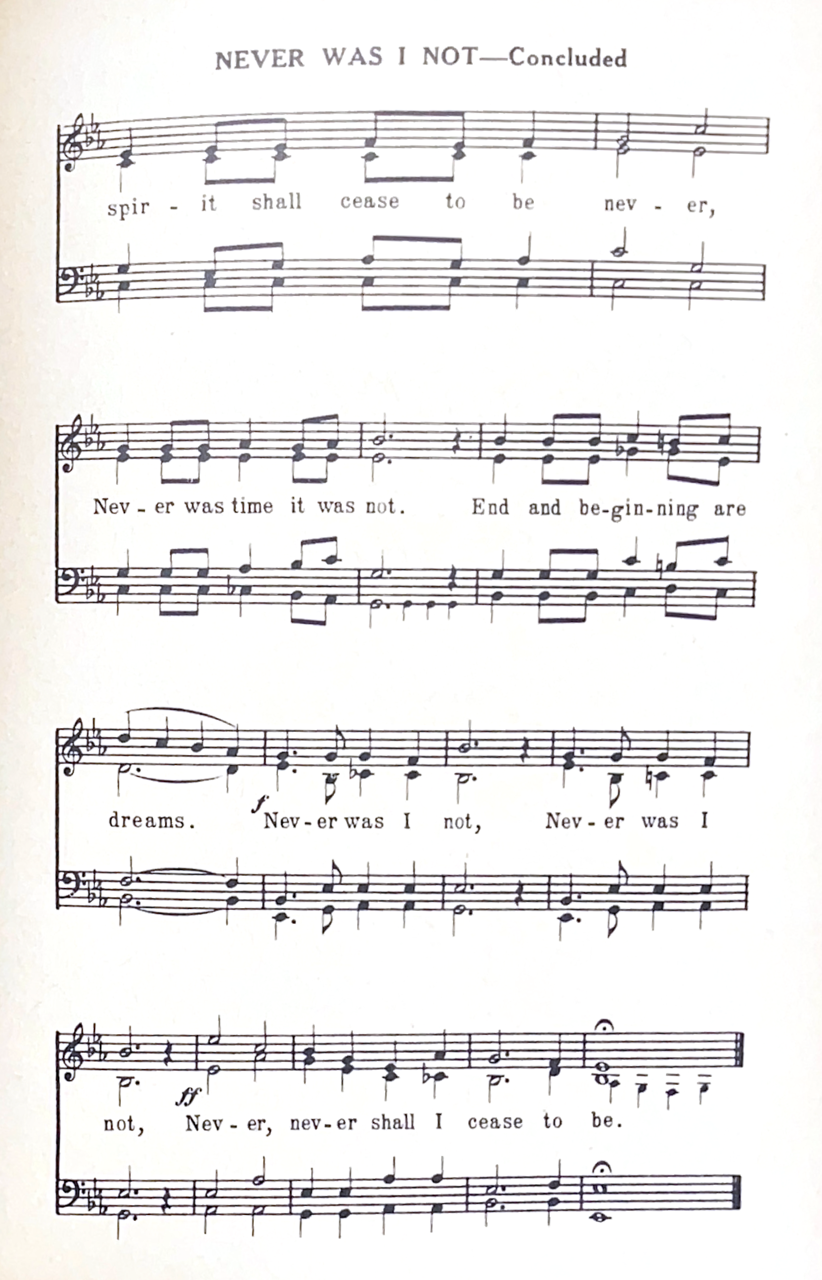

- NEVER WAS I NOT220

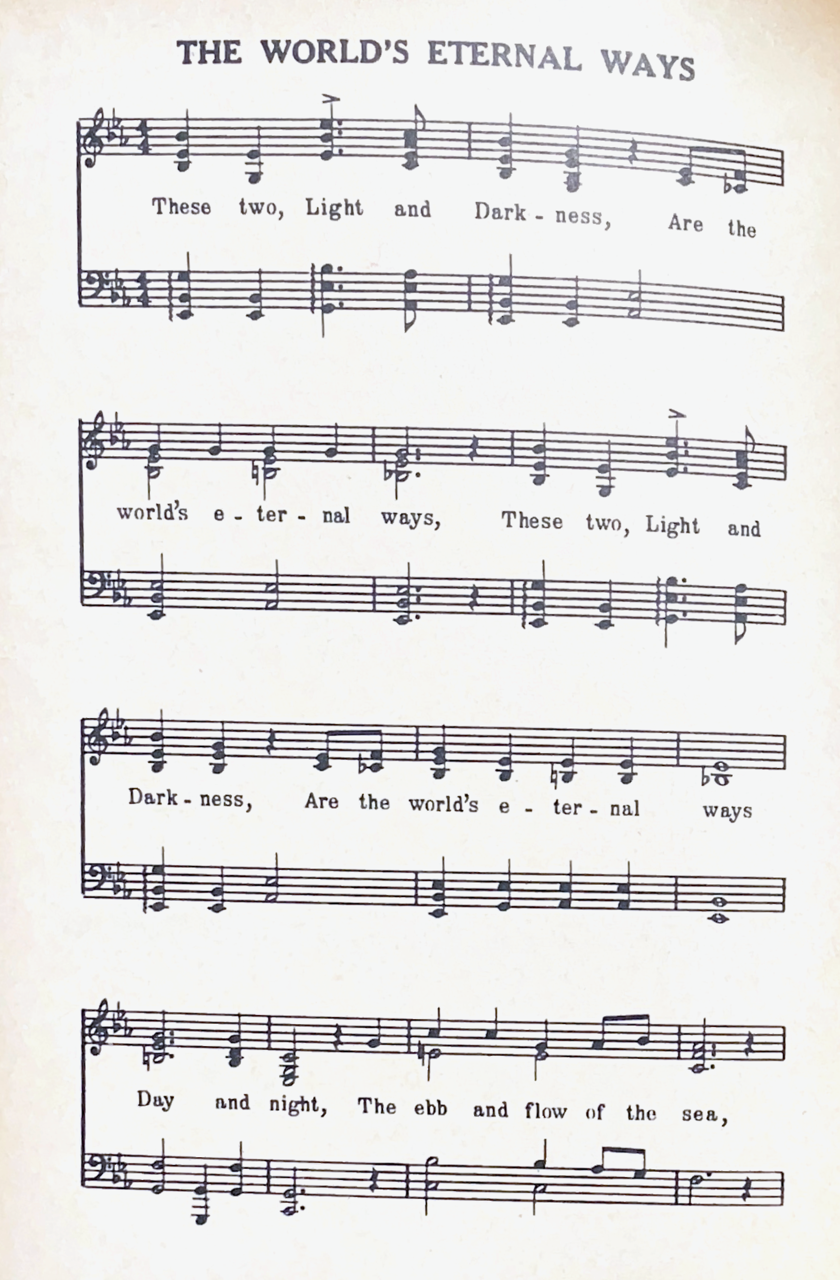

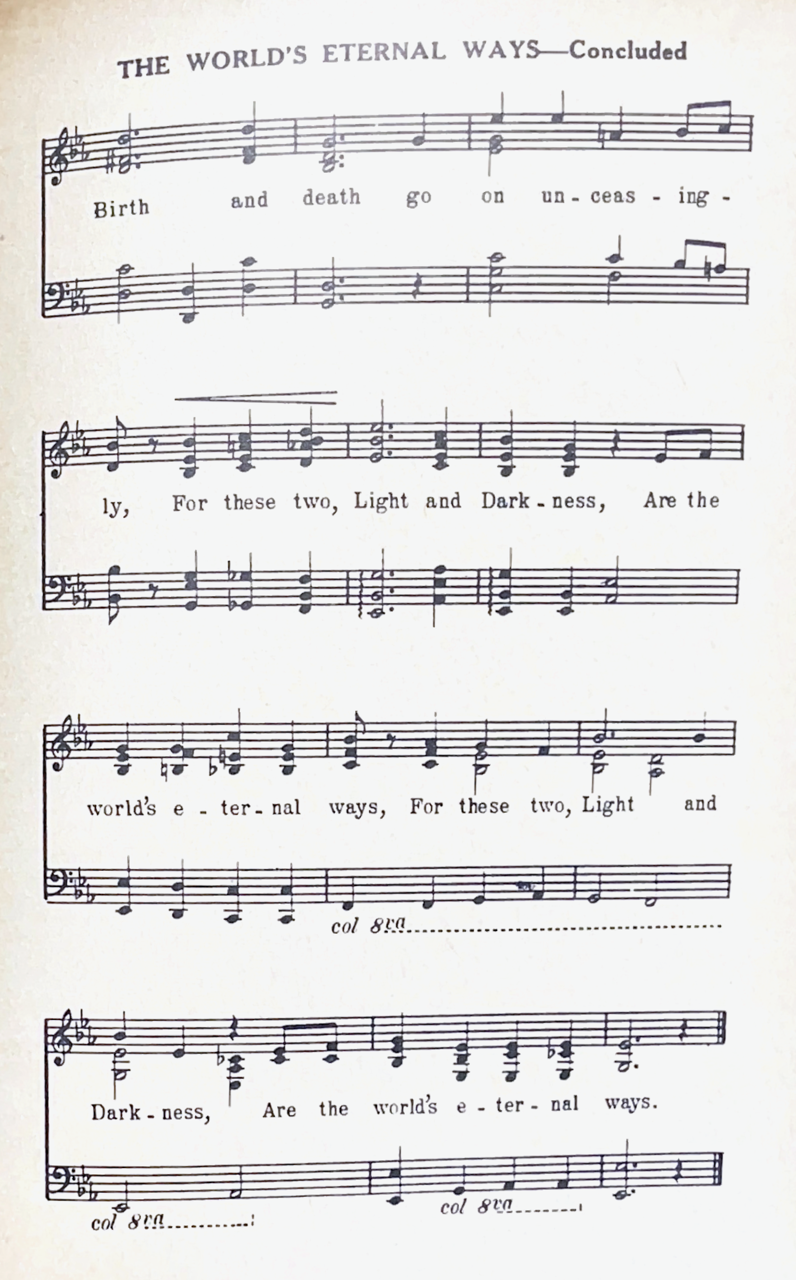

- WORLD'S ETERNAL WAYS222

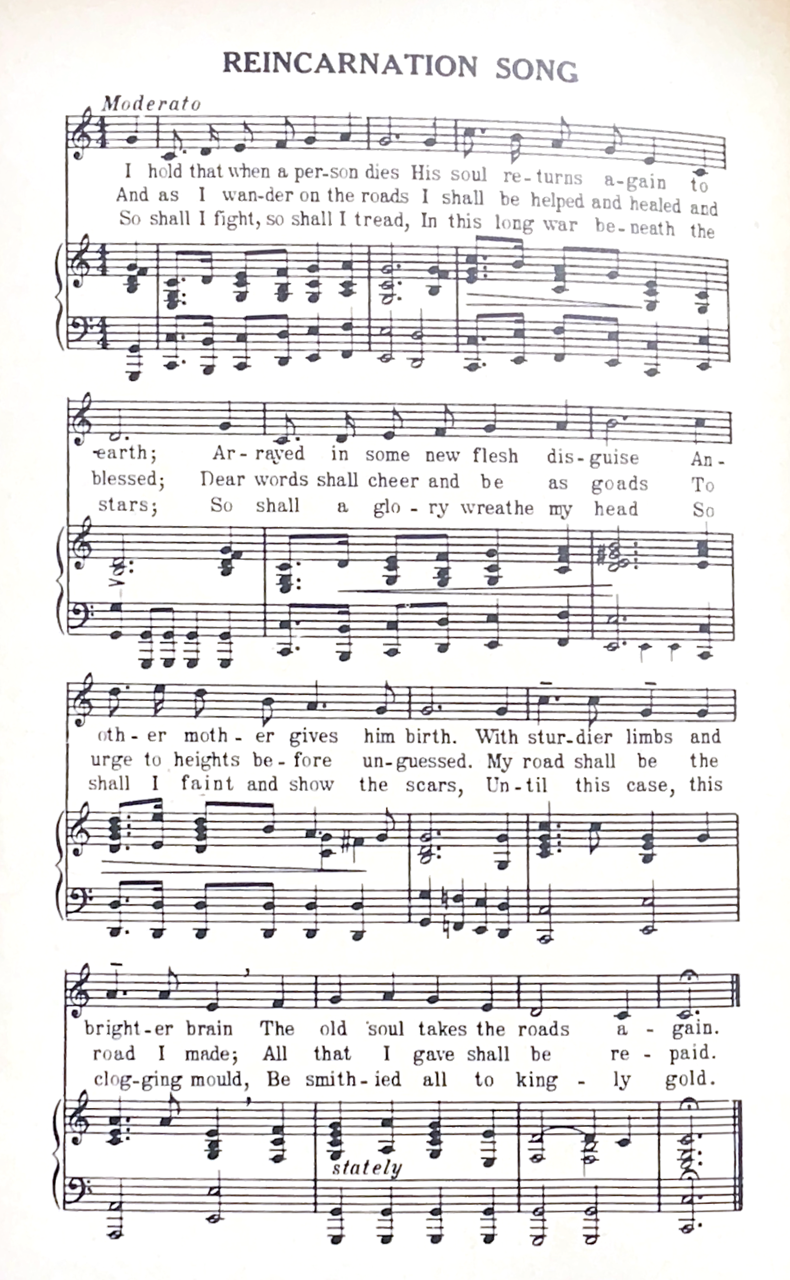

- REINCARNATION SONG224

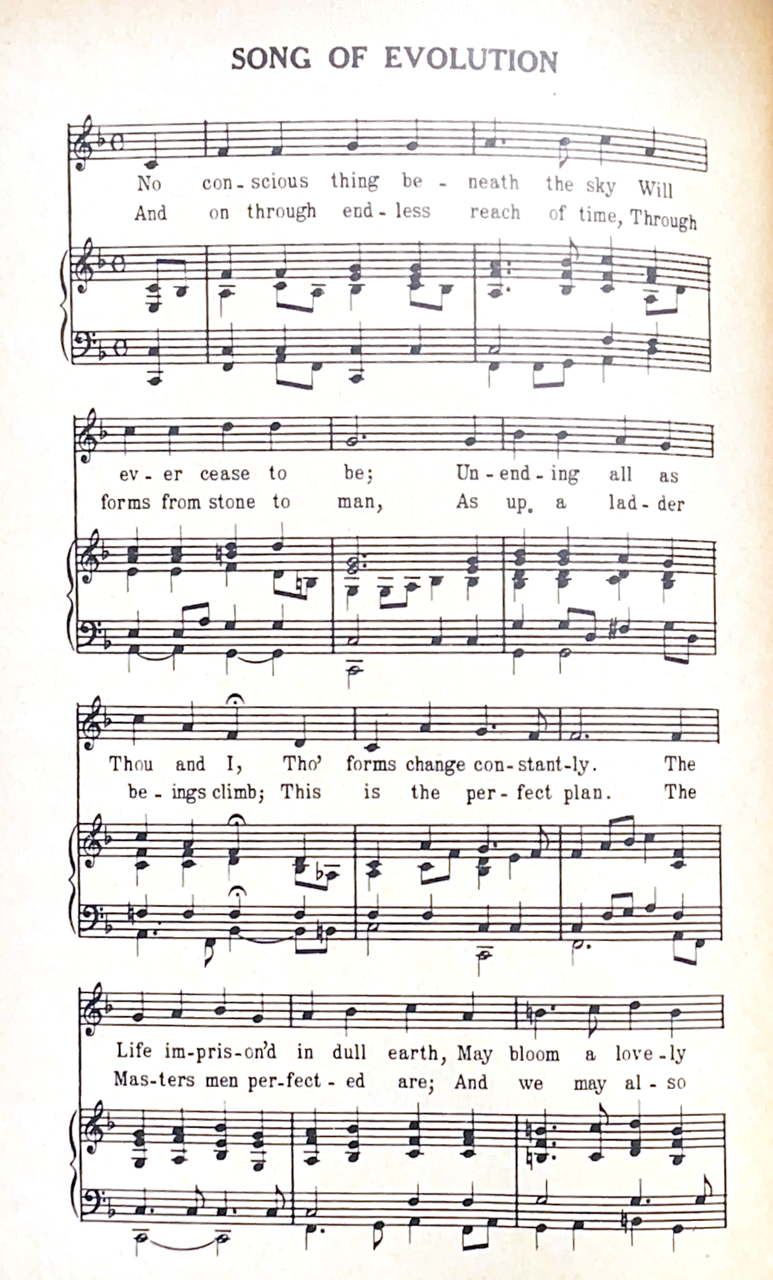

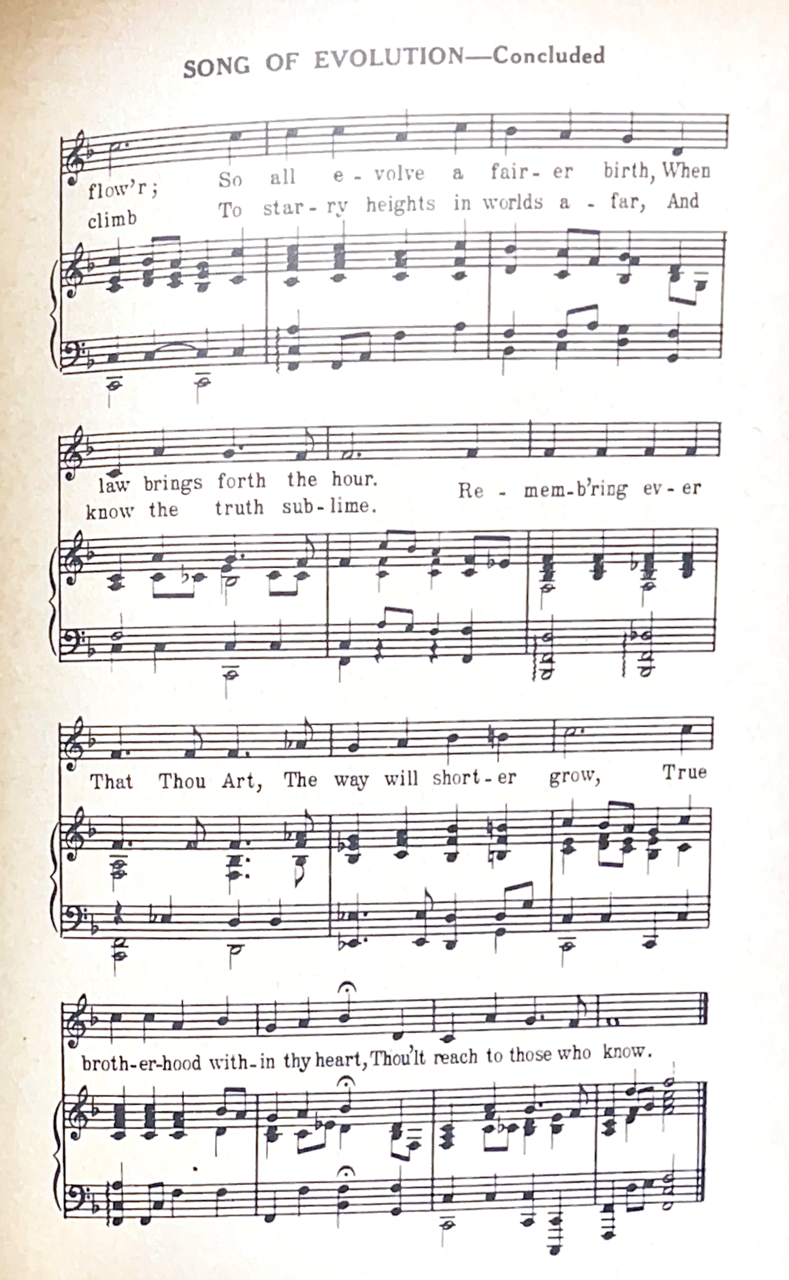

- SONG OF EVOLUTION226

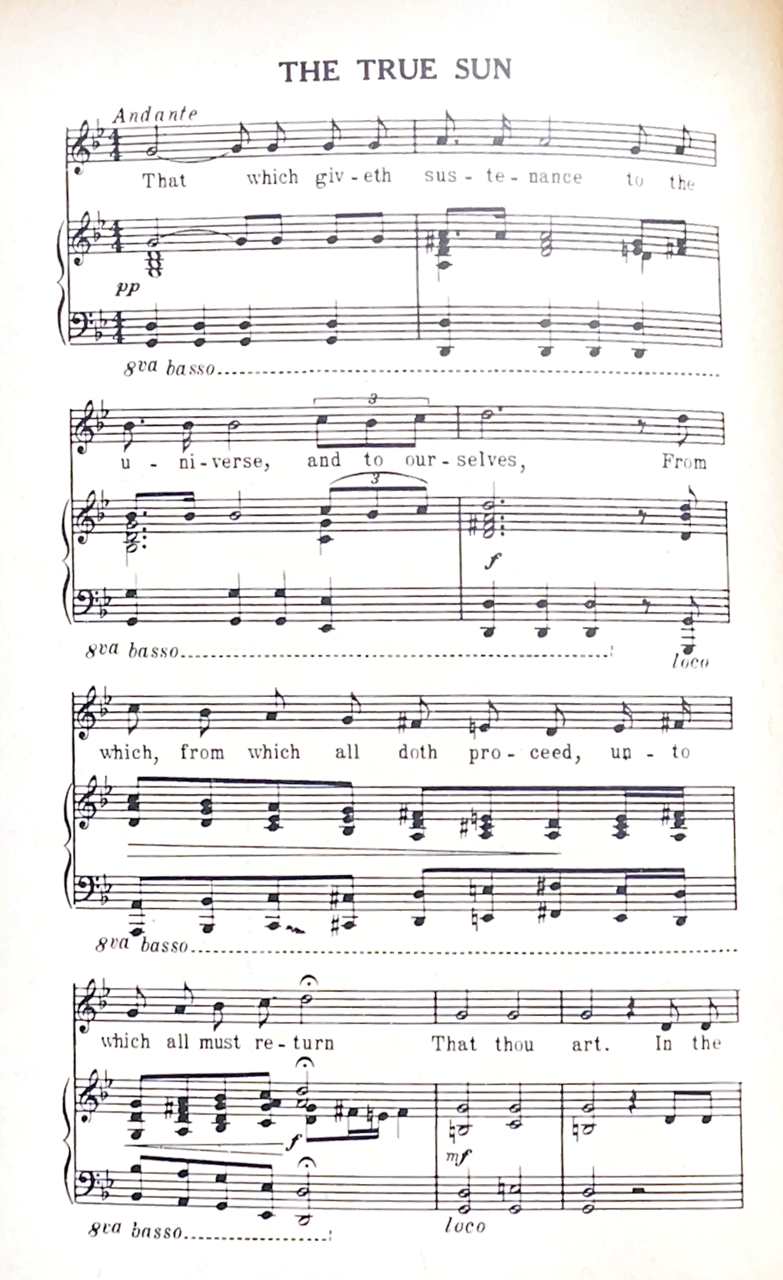

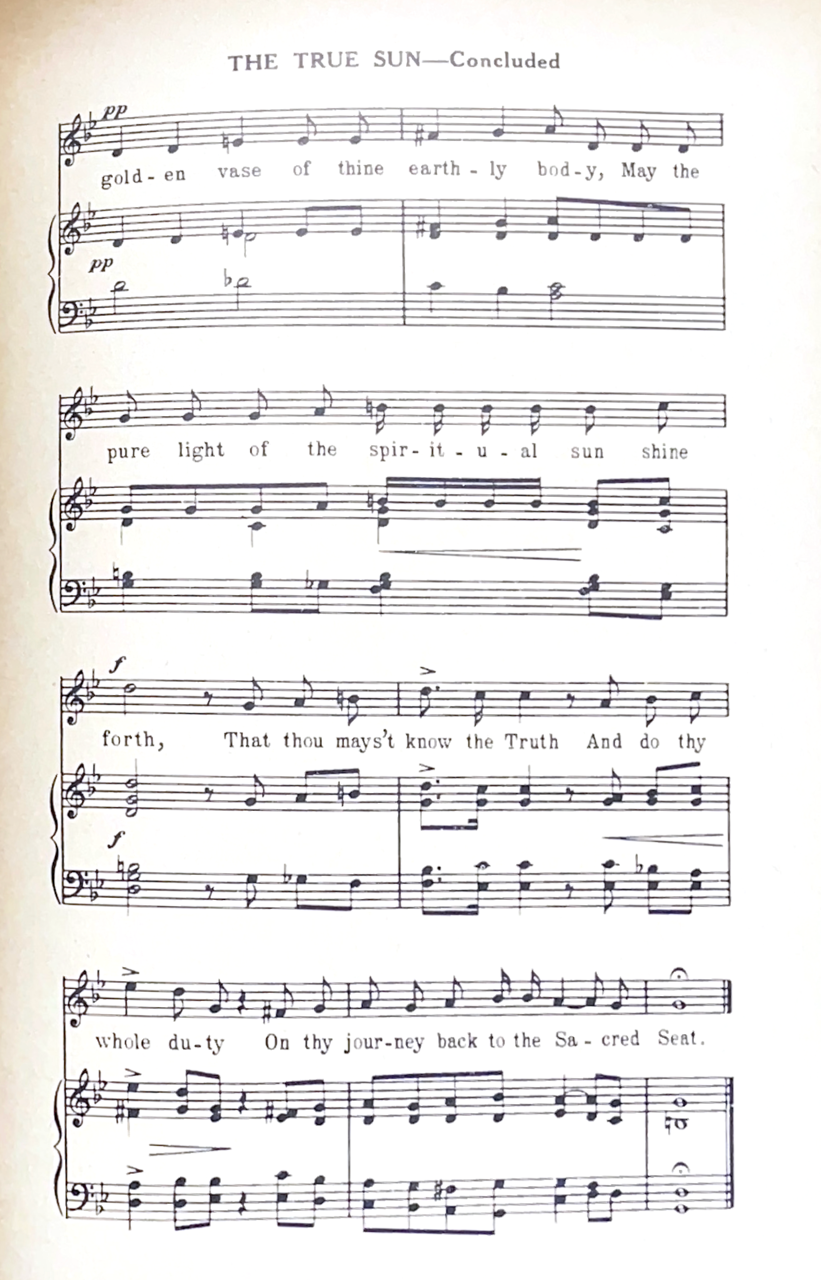

- THE TRUE SUN228

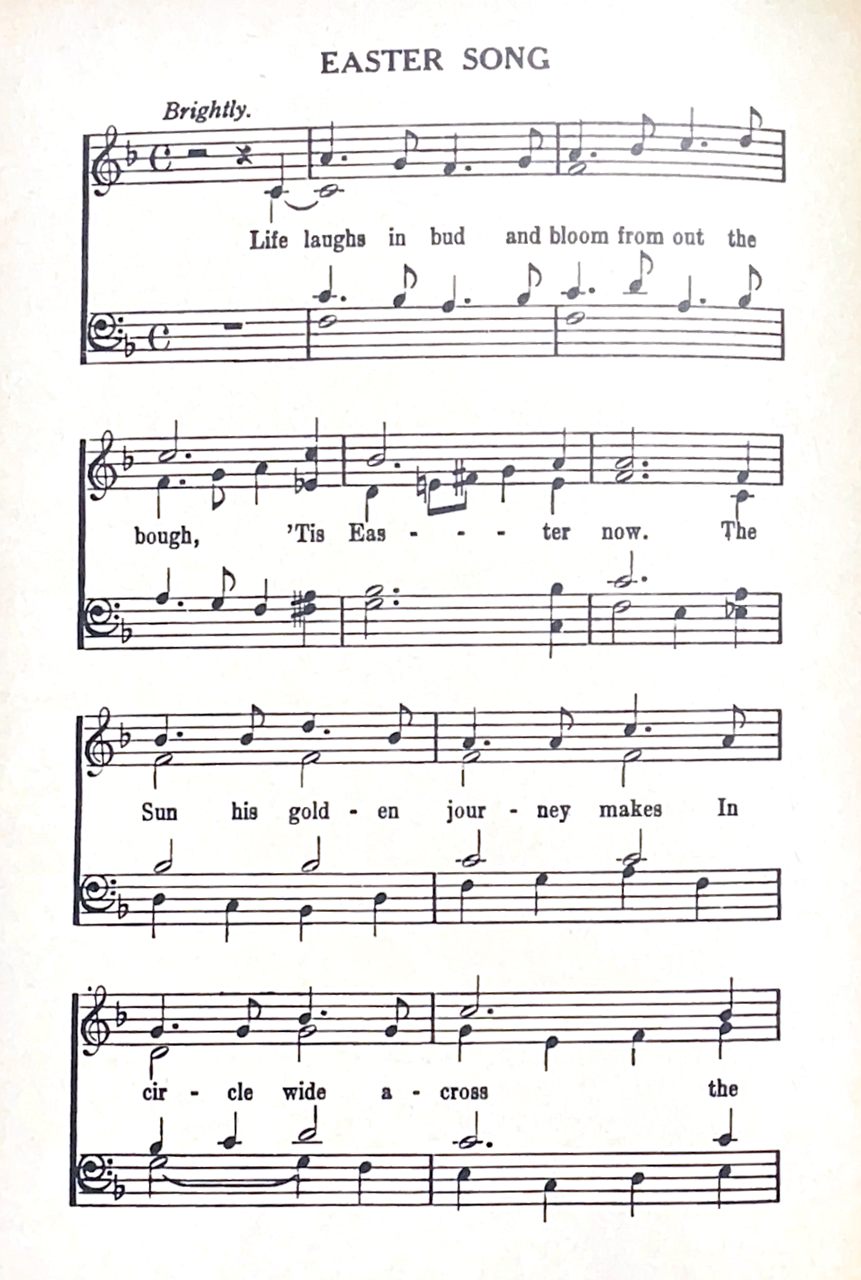

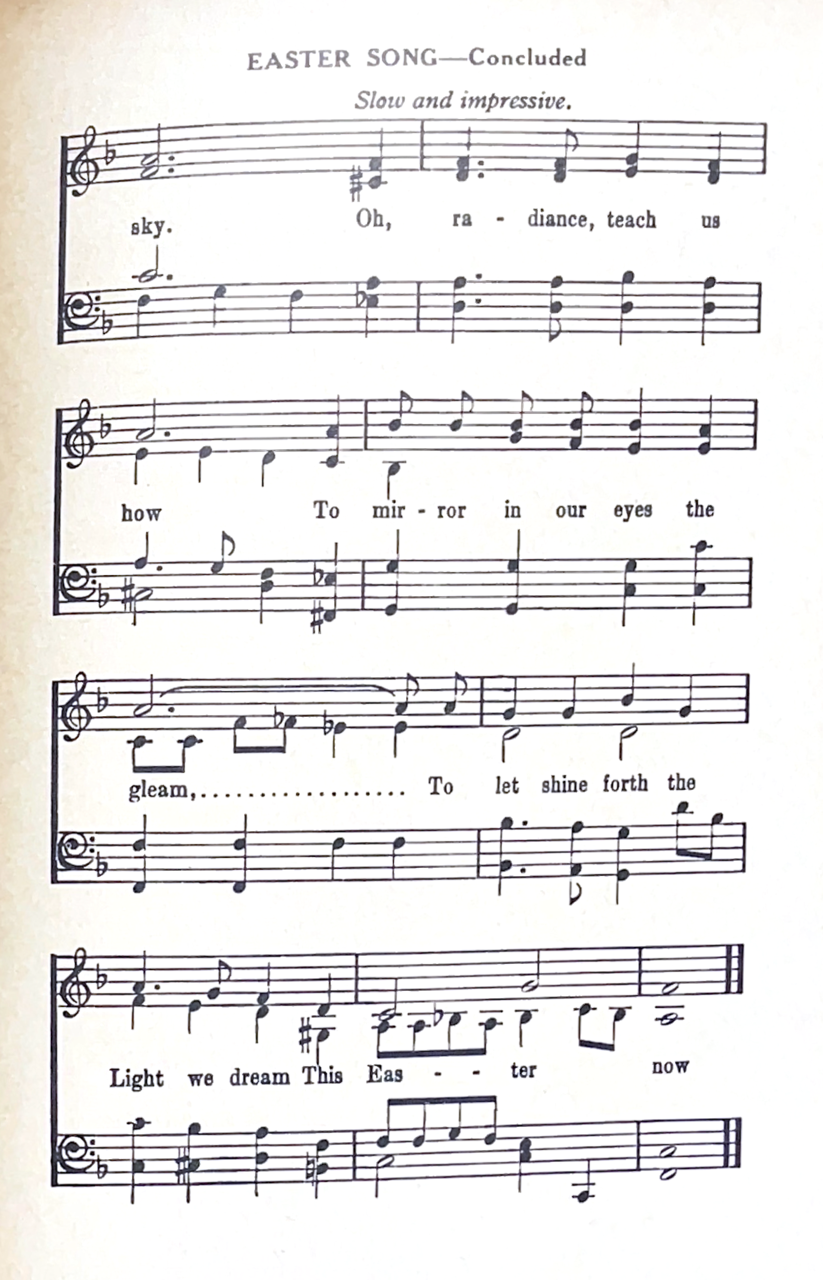

- EASTER SONG230

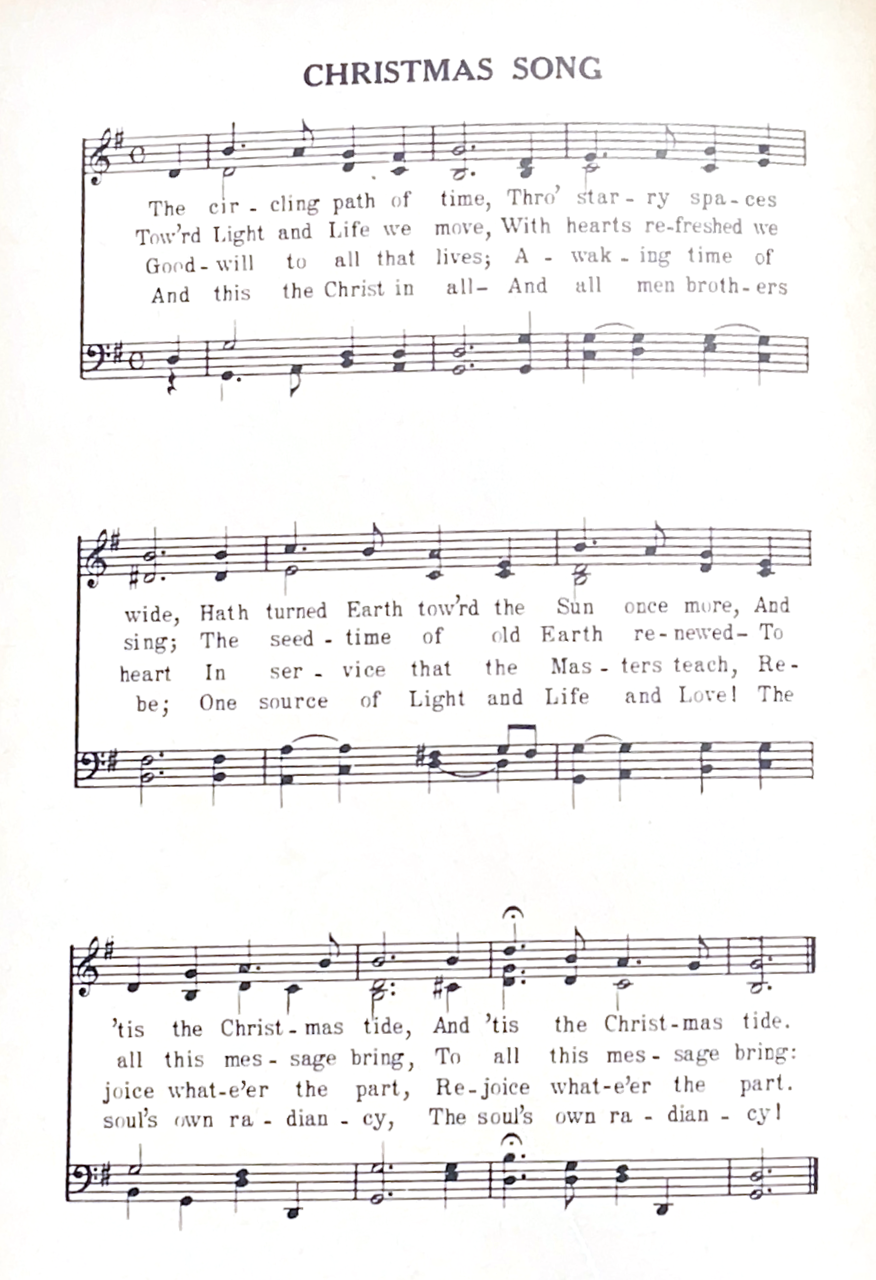

- CHRISTMAS SONG232

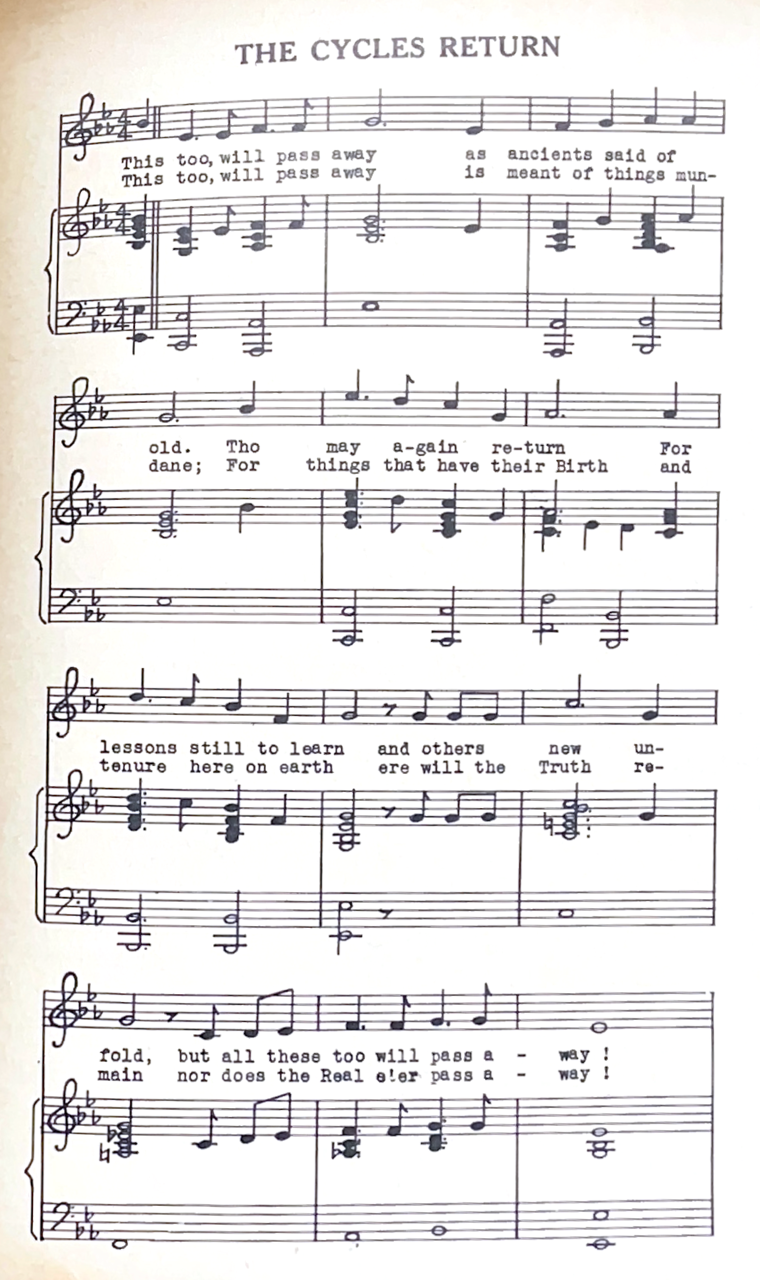

- CYCLES RETURN232a

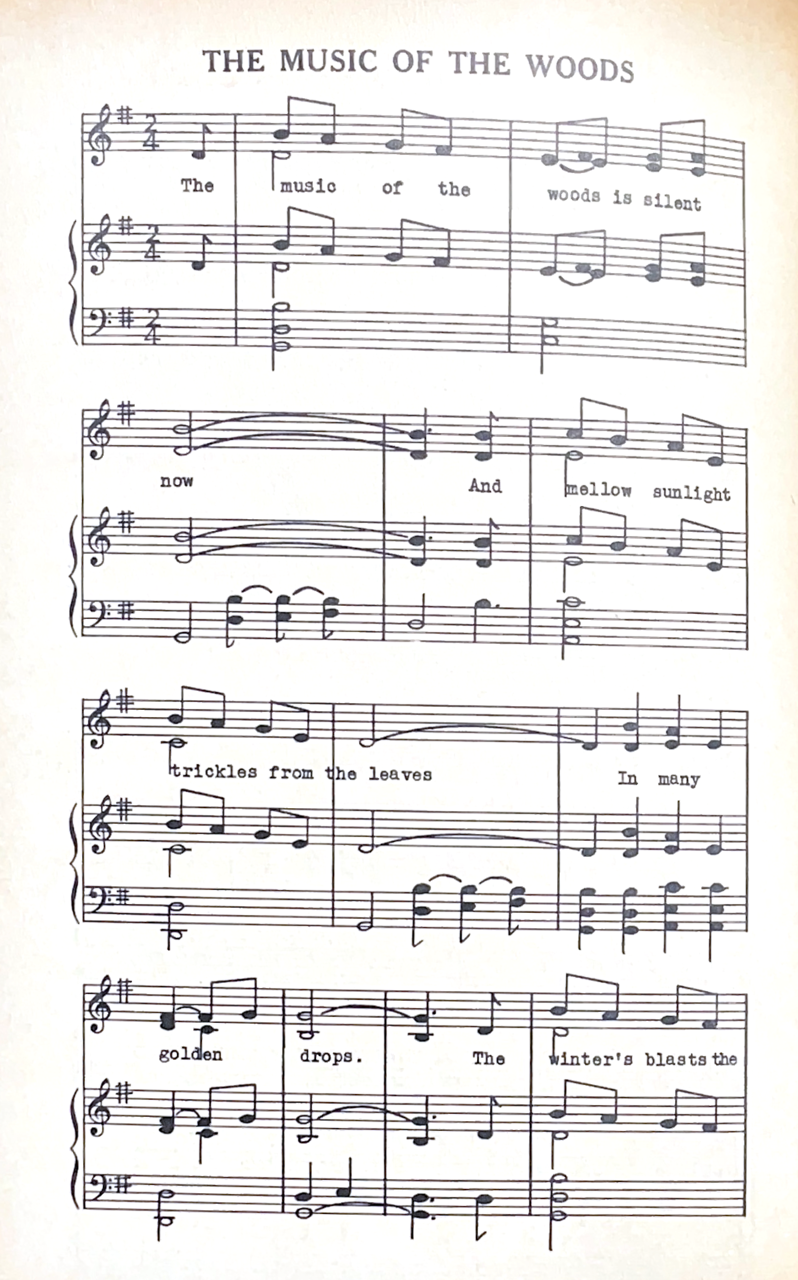

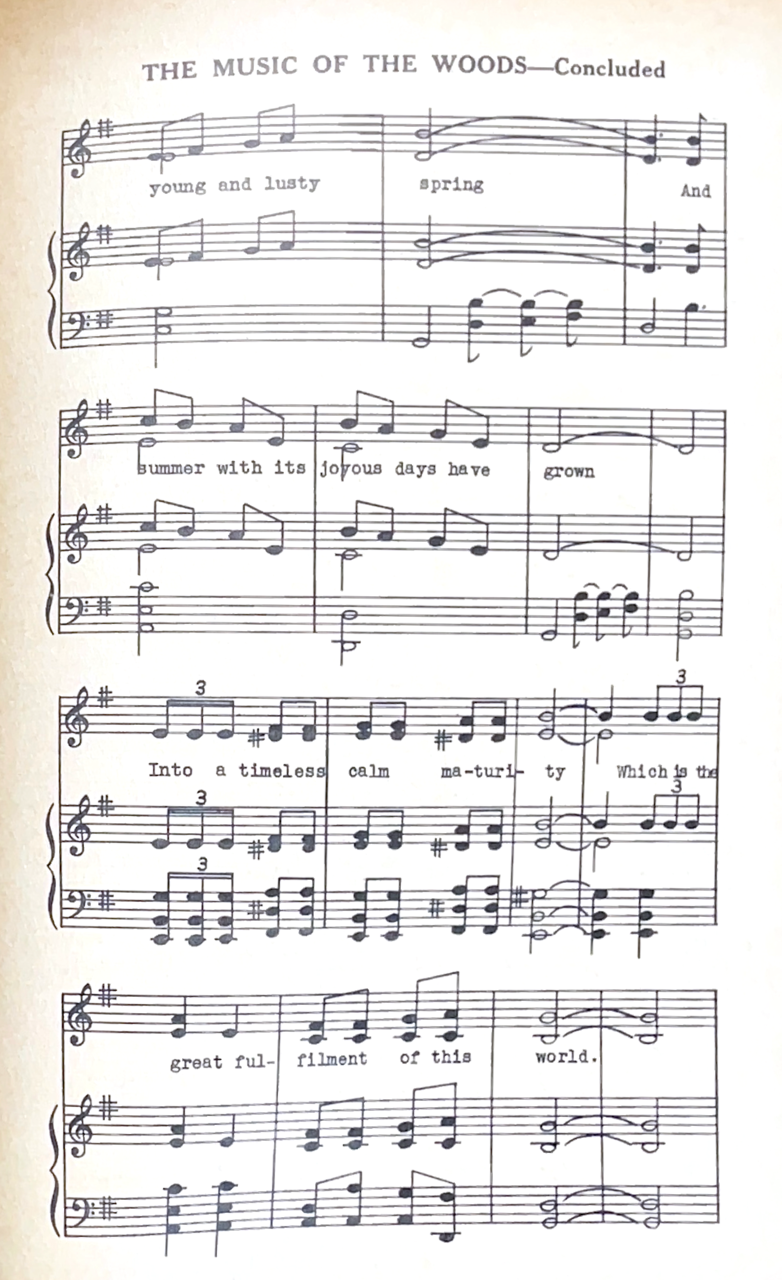

- MUSIC OF THE WOODS232b

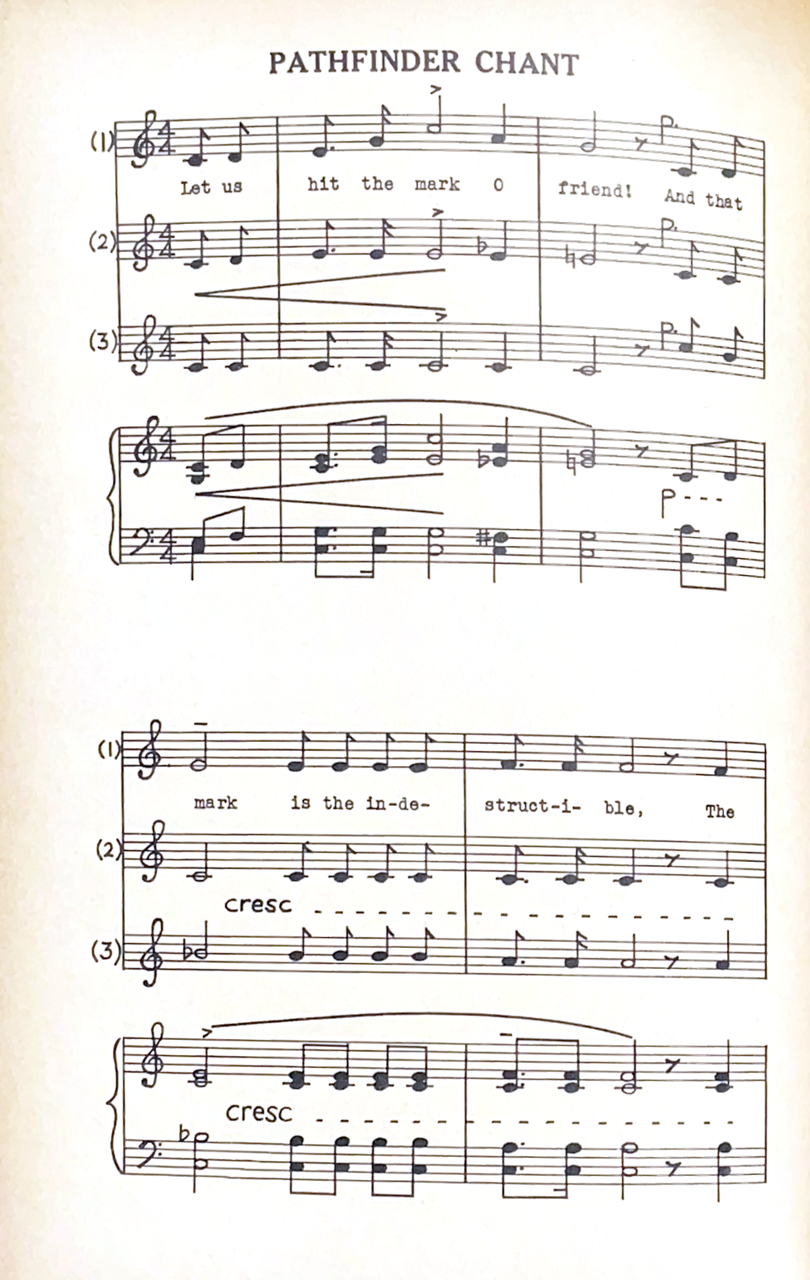

- PATHFINDER CHANT232d

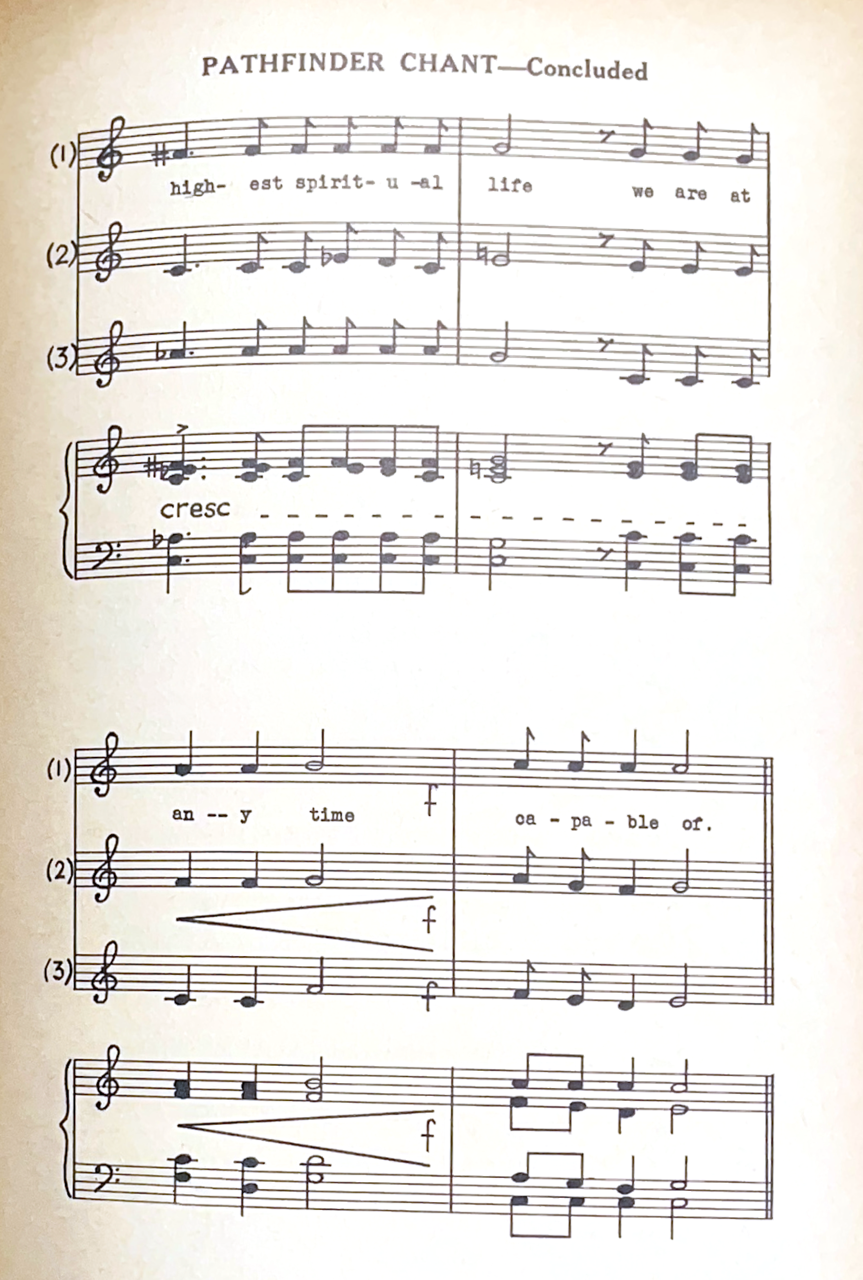

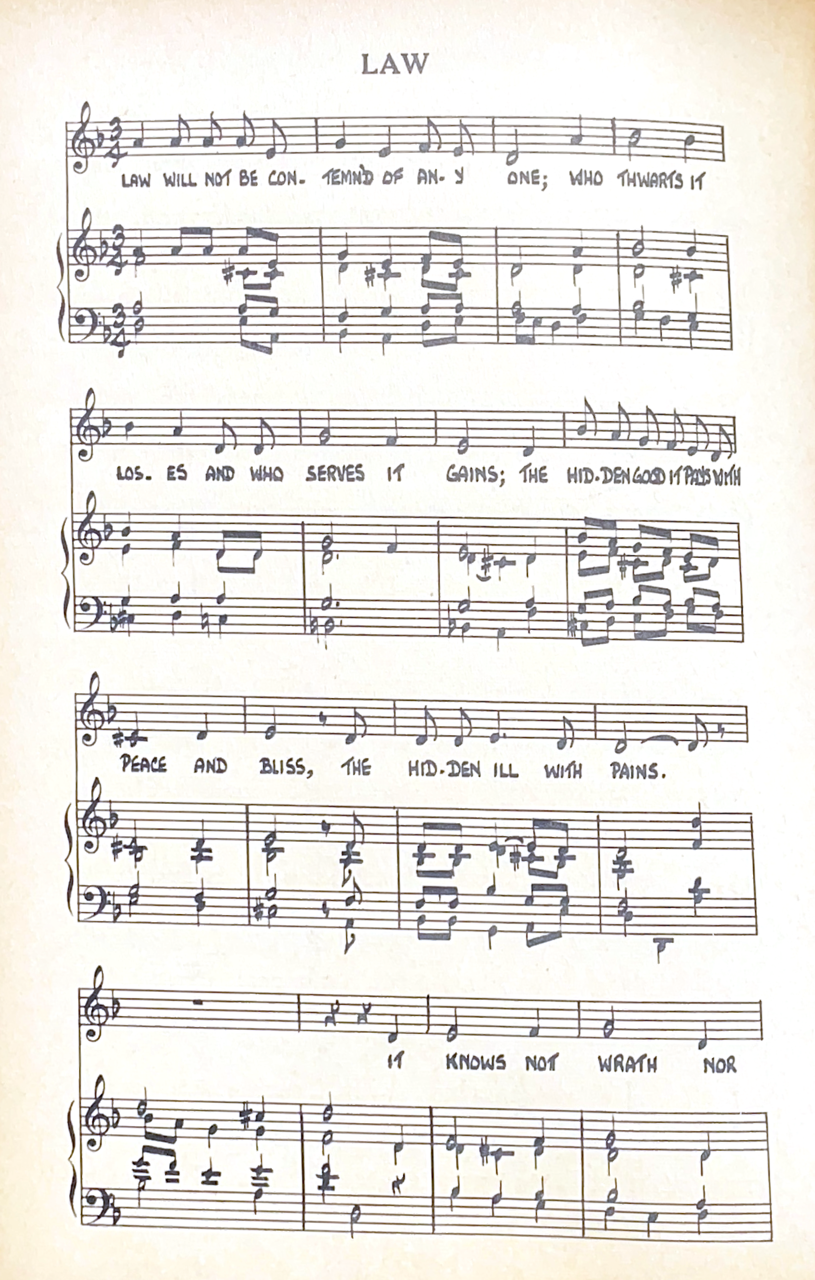

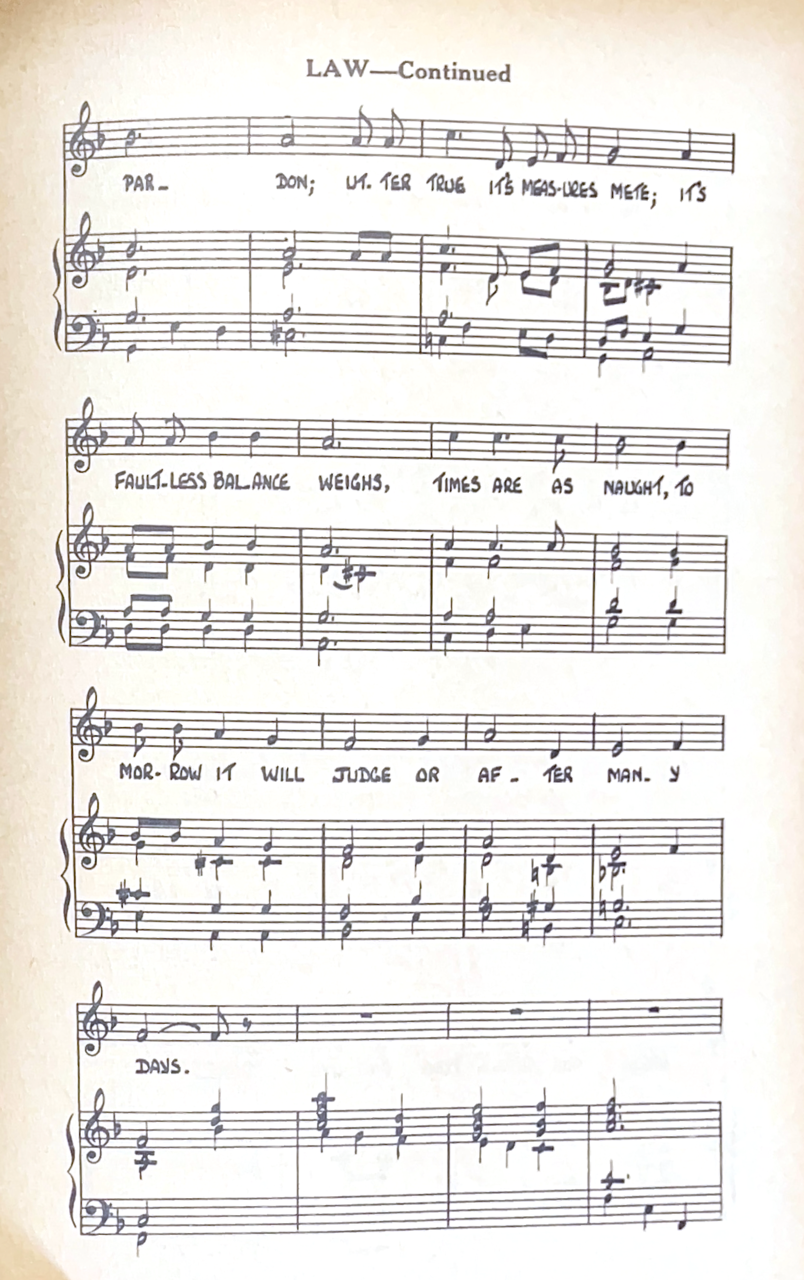

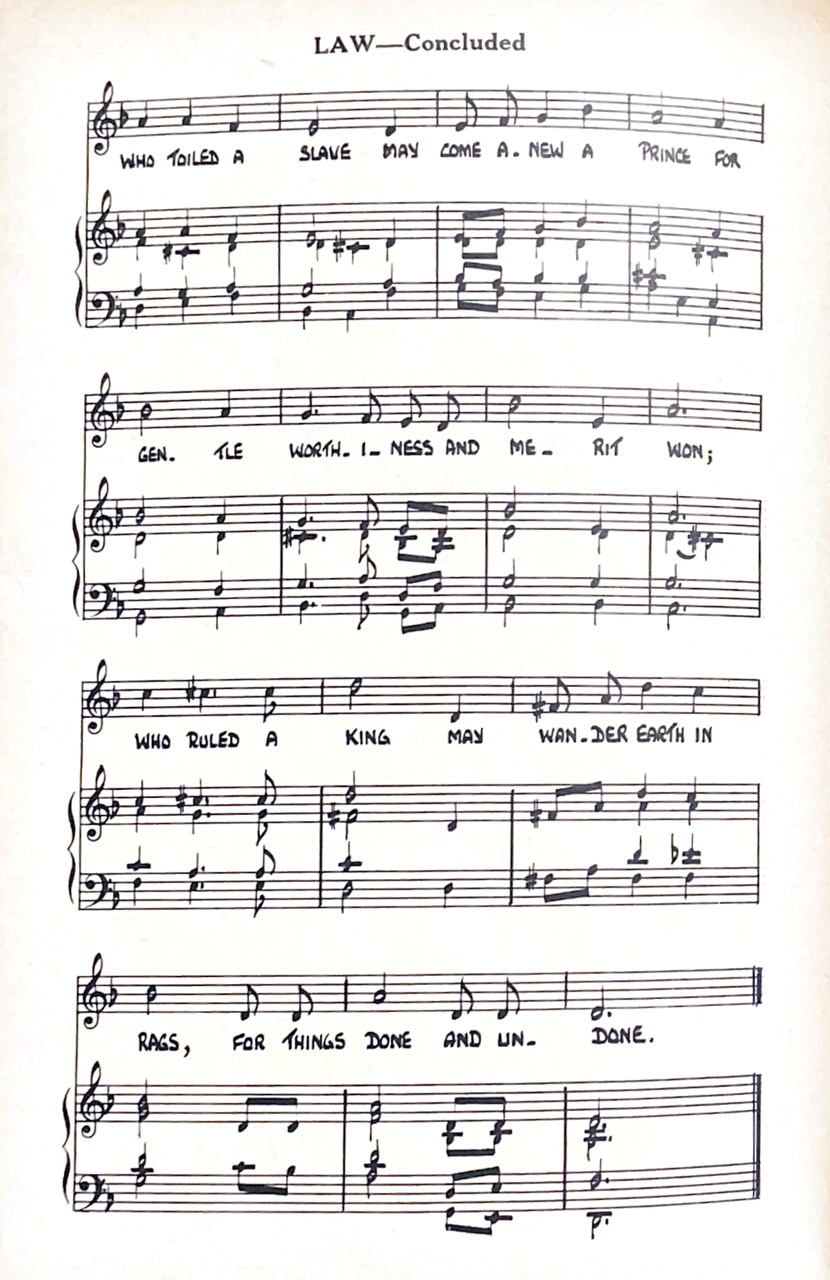

- LAW232f

- LESSONS FOR SPECIAL DAYS

- CHRISTMAS234

- EASTER252

- MARCH 21st, 1896265

- WHITE LOTUS DAY279

- DECLARATION OF THEOSOPHY SCHOOL295

PREFACE

Once, long ago, a boy said to his mother, "Mother, I don't know if I believe Theosophy is true." And she replied, "Why should you believe it, son? Either you know it, or you don't know it. Theosophy is not to be believed but learned, then proved by each one for himself, by doing it.

"Those we call Great Teachers knew. Those who only believed were followers, who first repeated the Teacher's words, then forgot. Because they were only half-taught, and because the Teachers: Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, never wrote their teachings down. Those who believe in Jesus go to pray in churches, to a 'God' outside and far off from themselves. Not so did Jesus. If they tried to prove by doing what Jesus taught, they too, would know Theosophy. Just listen to what Theosophy teaches, son. And look, and learn.

The boy did not answer, nor did he object; but, he began to think about Theosophy; he began to weigh and measure by it what he heard at school, what his friends discussed. And he thought, "Why, it isn't reasonable for a God to be up in the sky, who gets angry or is pleased. I can be angry or be pleased myself!

And it isn't reasonable that human beings descended from monkeys, because monkeys don't walk, and monkeys don't talk." Finally he said to his mother, one day, "Well, mother, even if Theosophy shouldn't be true, I don't know anything else that is even reasonable. I want to know Theosophy."

The Eternal Verities are the eternally true things true ideas of the universe, of all Nature, and of ourselves. This boy learned them. So can you!

November 17, 1940.

LESSON I

THE PATH

MEMORY VERSE: "Children of Light, as ye go forth into the world, seek to render gentle service to all that lives"

We all know what a path is. Have we not seen sometime a path beside a river? Another, across the meadow? Another, through the woods? The path of the Sun each day through the sky, and best of all, the path that, winds up hill and turns out of sight from where we are, and that makes us eager to go on to the next bend and the next! Some day, we say, we shall set forth and make the journey to the end of that road, even if it takes a week. But, there is another kind of path than paths we see. It is a secret path, and each one has his own. Each one goes on this path without moving his feet, yet, never stands still, for it is the path of the inner self, who thinks, and feels and chooses and remembers, and imagines, all unseen by any other. This Path lies right in our own home, and wherever we go forth from home to any other place. This Path is in our schoolroom, at work and at play, every day and all the time, both awake

and asleep. Even asleep, we are on this journey, though we don't move away from ourselves. If we did, we wouldn't wake up again, nor remember what we dreamed last night!

The journey on the Path is for all of us, whether we are rich or poor, or wise or foolish — not only for kings, great heroes, and mighty warriors, known of old. We are on the Path right now, and even though we may not move to the sound of trumpets, and though we have no seven-league boots. But, where does our Path lead? What is the journey for? How do we know we have chosen the right Path for us? Can we not see ahead more clearly than the man who started on a search the world around to find a simple four-leafed clover? For, when he had grown weary and old with failure, he came back to his little cottage, and found his own door-yard Sweet and green with nothing but four-leafed clovers.

Yes, we can know, because all men down through the ages have been on the same Path, have made the same journey. Some have left the trail-marks for us, so that we, too, may find as they did, the Truth, the Light, the Self. Is it to be found in some particular land, and in no other? No, for this is the mystery of our very selves we. Seek, and we can find it only

because we are the Self who seeks his own Light and Truth. We seek Self-Knowledge. If we do not seek, we shall not find it, and coming to our journey's end, we shall find there worse than nothing.

Many people do not know that most of the ancient legends and epics tell about this Path — about the search for the Light of Knowledge. Have you read of the Greek Jason's search for the Golden Fleece? And what adventures and difficulties he went through in order to keep it, once it had been found? Have you read of the Twelve Labors of Hercules — how he killed the Nemean lion and the Hydra-headed monster? How he captured the dog Cerberus, and cleaned out the stables of Augeas? These, and all his other labors were trials and tests for the Hero, Hercules, which he had to pass in order to know his weakness and his strength, not only physically, but also in mind and heart. And then, he could help others.

Do you remember how the great Greek Hero, Achilles, captured twelve cities, but was not able to control his anger at his King Agamemnon? Do you suppose that anger was the "heel" which the goddess could not make invulnerable, when she dipped him in the river Styx? Not Achilles, then, but Ulysses with his "wooden horse" finally captured Troy! It

was Ulysses, then, who received the armor of Achilles, and started back to his home in Ithaca.

It was Ulysses, then, who received the armor of Achilles, and started back to his home in Ithaca. Yet, what did his adventures with the lotus-eaters, and the Cyclopes, and Circe mean? What were the perils of Scylla and Charybdis? Detained so long on the island of Calypso — can we think he, too, had an "Achilles' heel"? King Arthur of old England, also, had to slay terrible monsters, and to win many battles as a valiant Knight. King Arthur's Round Table was one at which peace and harmony alone could rule. His Knights were banded together to give help and protection to the poor and defenseless; to help each other at need; but not to fight among themselves. Only thus, would ever they be able to find the "Grail" — the symbol of Self-Knowledge. In ancient Egypt, those men who built the pyramids went on pilgrimages of service to other lands, to faraway Greece and Erin. They, too, fared forth as "Children of Light" to gain possession of the Crown of Knowledge; to discover for themselves the answers to the age-old questions that each one asks today: "Where did I come from? Why am I here? What am I? Why all other beings and things in the world? "Theosophy has an answer for these questions. They are questions asked by the Self,

here in a body. The Self can answer, and must answer, also, but, Theosophy is the guide-book and helper here, it gives the signs, the land-marks, which the Self will recognize and which will lead us on the Path of Knowledge Unless there were Knowers of the Truth, there would be no Theosophy. Theosophy means divine knowledge, from the two Greek words, theos- god, sophia- wisdom We may take "gods" to mean, in a true sense, beings of highest knowledge When we learn what they know, we, too, shall be "gods," possessing god-like knowledge, here. We already know in our inmost Self, but the knowledge is in prison. We must know how to let the light shine through. And, first of all, we must want to know.

Now, supposing we would like to have the knowledge of Theosophy, but say, "I don't like to learn this, I will learn this, but I won't learn that; I'm going to wait ten years before I begin; I'll help some day, but I want to do my own way now" do you think any teacher, however wise and kind and patient, could make us see? They would not force us to see if they could! And do you think the kind of guidance such wise ones give will make us better, or worse, scientists, physicians, lawyers, teachers, painters, musicians, aviators, engi-

neers, mechanics, truck-drivers? Better or worse fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters' friends?

Surely, if Theosophy is the truth, it would be foolish to find fault with it — at least, until we know what it is, just as it would be foolish for us to find fault with the multiplication-table, until we know it and how to use it! So, shall we not try to be learners, realizing that all the truth in the world is useless to each one, unless each one knows it! What someone tells us, and we merely remember in words, is not our own knowledge. But, if someone else who knows shows us how to get the same knowledge, and we follow his directions, do as he did to get it — can anything hinder us from our knowing, also? Theosophy is the record of those who know things as they are. It points the way to think and to live, so that everyone may become wise. For Truth is the same for those of white, or black, or red, or yellow skin; it is the same for learned and ignorant; the same for young and old. This is why the Soul must know it.

Theosophy is the wisdom of those who once were like ourselves, who determined they would know, who asked all Nature to teach them, and who followed the Path that other Wise Ones had pointed out to them. Theosophy is the wisdom of such men as Krishna,

Buddha, Jesus; it is the same wisdom taught by H. P. Blavatsky and William Q. Judge. It includes and is greater than any kind of knowledge men find in books. It includes the science of mathematics, of astronomy, of m music, of architecture, of engineering. It is the soul of great literature and art. It is the true source of education. On it alone will true government be founded. The Knowers of this real Knowledge are living Men, whose only concern is that all men may likewise come to have wisdom. They are called Masters of Wisdom.

To us all, as learners, they say the first step of direction upon the Path of Knowledge is to be found in our Memory Verse. Could we not go forth in the morning doing "gentle service" as "Children of Light"? Can we not each night go as "Children of Light" to the land of sleep and dreams, and to our own place where we are our Highest Self?

TO THINK ABOUT

- What kind of a Path does Theosophy tell about? Where is it?

- What does the story of the man who searched for the four-leafed clover mean?

- What is the purpose of the journey on the Path?

- What is the meaning of "Achilles' heel"?

- What does the word "Theosophy" mean?

- Can anyone make us learn? Why not? How do we learn?

- Who are the Masters of Wisdom?

ONE WHO FOUND THE GEM

"In the land of the Wise Men there dwelt a young man. Many years had he labored in a strange mine: the 'Mine of the Priceless Gems'; hopefully, bravely, but fruitlessly. He had long known that he who should find the Master Stone would be free, full of peace, and dig no more, for nothing better could be found. He also knew that he who found the stone should seek to share it with all men. "Many small stones had he found, but they were laid aside to be used when the great stone was reached. "Silently and steadily he worked on, until one gloomy day when he had grown so weak that he could make but one more effort, that effort was rewarded, and before him lay the great gem. Weary, weak, but joyful, he gathered it into his bosom, and went forth to share it with others; for he who told not of his gem, or shared it not with all men, must lose the stone.

"Far he wandered, telling his wonderful story, the finding of the Priceless Stone — the stone that made men greater, wiser, more loving than all things living; the stone that no man could keep unless he gave it away.

"Far he wandered in his own country, seeking to tell his story and give of the Stone to each one he met. Silently they listened gravely they meditated and gently they said to him: 'this is Kali-Yuga, the Dark Age. Come to us a hundred thousand years from now. Until then — the stone is not for us. It is Karma.'

"Far into another land he wandered, ever trying for the same end. Gravely they listened, quietly they spoke: 'Peace be with you. When the Lotus ceases to bloom and our Sacred River runs dry, come to us. Until then we need not the stone.'

"Over the seas unto another land he went, for fully he believed that there they would hear and share with him. The many days of wandering and the long journey across the sea had made him thin and ragged. He had not thought of this, but as he told his story he was reminded of it and of many other things, for here the people answered in many ways and not always gently.

"Some listened, for his story was new to

them, but the gem was uncut, and they wished it polished.

"Others paused and desired him to tell his story in their tents, for that would make them exalted and famous, but they wanted not the gem. As he did not belong to their tribe, it would bring discredit upon them to receive anything from him.

"One paused to listen and desired some of the stone, but he desired to use it to elevate his own position and assist him in over-reaching his fellows in bartering and bargaining. The Wanderer was unable to give any of the stone to such as this one.

"Another listened, but inasmuch as the Wanderer refused to make the gem float in the air, he would have none of it. "Another heard, but he already knew of a better stone, and was sure he would find it, because he ate nothing but starlight and moonbeams.

"Another could not receive any of the stone or listen to the story, for the Wanderer was poor and ragged. Unless he was dressed in purple and fine linens and told his story in words of oil and honey, he could not be the possessor of the gem.

"Still another heard, but he knew it was not the gem. As the Wanderer had been unsuccessful before, surely he could not have found

the stone. Even had he found it, he could not have the proper judgment to divide it. So he wanted none of the stone.

"Near and far went the Wanderer. Still ever the same. Some wanted it, but the stone was too hard, or not bright enough. He was not of their own people or was ignorant. He was too ragged and worn to suit their ideas, so they wanted none of the stone.

"Saddened, aged and heart-sore, he wandered back to the land of the Wise Men. To one of these he went, telling of his journeys and that no man would share with him the magnificent stone, and also of his sorrow that he too must lose it.

"'Be not troubled, my son,' said the Wise One, 'the stone is for you, nor can you lose it. He who makes the effort to help his fellow man is the rightful owner and still possesses the entire stone, although he has shared it with all the world. To each and every one to whom you have spoken, although they knew it not, you have given one of the smaller stones which you first found. It is enough. When the Master Stone is cut and polished, then is the labor of the fortunate possessor ended. The long journeying and weary wandering, the sorrow-laden heart and tear-dimmed eyes, have cut and polished your gem. Behold, it is a white and a fair stone!'

"Drawing it from his bosom, the Wanderer gazed into the wonderful light of the stone while an expression of great peace stole over his face. Holding the gem close to his bosom his eyelids closed and he fell asleep, a wanderer no more."

RAMESE *

* William Q. Judge.

LESSON II

THE FIRST TRUTH — TRUTH

MEMORY VERSE:

"We have come in search of Truth,

Trying with Theosophy

Door by door of mystery,

Learning from Theosophy.

We are reaching through all laws

To the garment hem of Cause,

THAT, the endless, unbegun,

The Unnamable, the One

Light of all our light the Source,

Life of life, and Force of force."

Truth is simple. Truth declares itself. When one says that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, we know it is so. Is there any way to argue about it? There is only one Truth about everything----about the universe and about ourselves. No matter how many and differing are the explanations of truth people give, the Truth remains ever the same, everlasting, unchanging. But, in Theosophy, the One Truth has three "faces," or "angles," or "aspects." We call them THE THREE TRUTHS. Perhaps, our fathers and mothers call them the "Three Fundamentals."

But they are made of the very same ideas! However great may seem to us now the mystery of many things, a real understanding of The Three Truths will bring an understanding of them, and of all things else.

Many names we have for THE FIRST TRUTH, yet not all names together can describe it. We could name what It is forever, and still not be done. Have we ever thought how we could keep on counting all our lives, and still there would be more to count? So, the words that describe It the least are the best words for our minds. When we say, THAT is the cause and origin of the universe and of ourselves, we can make no picture of a thing or person by it. We can only think, It is the Real — the One Reality. And when we say, It is Life — Spirit — Consciousness (this last so-very-long word is one we must think about much!), we can't see any thing in our minds to compare those words with. But, we can think of them together as One, and when we hear one of the words, the others spring up with it in our minds.

Now, if all things come from Life, Spirit, Consciousness, so did we! But, we aren't going to think, for all that, "my spirit," "my consciousness," "my life." Wouldn't it be foolish for a sunbeam out on the Pacific Ocean to say "my Sun"? Because everywhere else in the

universe would be sunbeams just as much a part of the Sun as that sunbeam. All the sun beams come from the Sun; there would be no sunbeams without the Sun. So, that sunbeam on the Pacific Ocean would be wiser to say joyfully to his neighbor sunbeam on the next wave, "You, too, are from the Sun. On the Atlantic Ocean are still more brother sun beams. Away off in the city streets, our brothers shine."

All men are our brothers, because the Life in us is the same Life as in them. All beasts and birds and reptiles and plants and stones are our brothers, because they, too, are alive.

You didn't think stones are alive? Well, they are. Have you never seen the spark flash from a stone, when struck by a horse's hoof? Stones don't move about as we do; they are not self-moving; but, inside the stone is a constant motion of whirling atoms. There wouldn't be that motion without Life. The same kind of inside motion is going on in that table before your eyes, in the very walls of the room. Because we are very still when we are asleep, we must not think no motion is within our bodies. The blood is circulating; the lungs are breathing, digestion is going on — not to mention other kinds of motion of our consciousness! Bars of iron and of steel seem not to be "alive," but,

how can we explain, if life is not there, that machines over-used are said to be "tired," and if allowed to rest long enough, will recover their former strength and efficiency?

Had you realized that plants have blood and nerves as we have? No, not the same kind of nerves and blood, of course, but a kind of blood (What do we call it?) that takes nourishment as ours does, and a kind of nerves that feel hurt or kindness as ours do. A great Hindu scientist, Sir ChundraBhose, made many experiments to prove this. So, we might ask ourselves how it is that flowers will grow for one person, and for another will wither away and die, though, apparently, both persons give the same care to the plants. You have wondered sometimes if dogs and horses and cats think, haven't you? Yes, they do in their way. But, it is not as we think. When a dog sees the stick its master has beaten it with the day before, he cringes; but, when the stick is out of sight, there is no thinking about the stick, nor what his master did with it. Some trainers of dogs have taught them how to say words. But, when the trainer is out of the dog's sight, the dog does not heed the directions of another trying to get it to say words. So, we have taught our hands to do many things, automatically; but, if we are asleep — not "there" — the hands are still. When

we are "there" again, and will to have the hands do the task, then the hands "remember." We can say, "I think that dog is thinking." But the dog does not think, "That is a boy, and I am a dog. That boy thinks in another way than I think." The dog sees many things, but it does not to itself think how one thing differs from another.

The real seeing is not with the eyes, but with the mind; it is within ourselves. When we shut our eyes and see nothing but blackness, we are there, knowing the eyes do not see the trees and flowers and houses which they saw but a moment ago. And then, we can remember them all, seeing them in our mind. We can also see an idea; but, this kind of seeing we may call "perceiving." The dog seems to know a great deal. But, it does not know that it knows. It sees a great deal with its physical eyes, but it does not see with its mind. It sees motions; it does not see ideas. Its "perceiving" is for the most part in feelings of hunger, thirst, heat and cold.

In the dog is the same Life as in ourselves. It sees by Light as we do, though only by certain kinds of light. It is conscious, but is not Self-conscious. The dog has not the kind of brain into which the Light of mind can shine. It can not say nor feel "I". It can not remem-

ber what happened last week; it can not plan something to be done next week. An animal caught by its leg in a trap will gnaw off its leg to get away. Then, it is not conscious of even its bodily self. But, even a tiny baby is conscious of its body-self; the babe knows when it is in discomfort and cries for attention. Very early it examines its fingers and toes; the babe really sees them. We boys and girls and men and women can see and understand all other kinds of beings, as well as ourselves. We can see and know that all are our brothers, because their life comes from the same One Life, the same One Spirit, as ours does. We are Self-conscious Knowers, Perceivers, Thinkers.

Have you ever noticed that it is not till about three that baby sister or brother begins to say "I"? Up to then, they speak of them selves as others call them — perhaps, "Baby" or "Bobbie" or "Jeannie." But, when they say "I," we know a real Person is with us. Have you ever wondered about that strange being — "I"? And did you think it was your body, and its clothes? Because it couldn't be, or it would be a different "I" every time you put on an other suit. Or, did you think it was your feelings? It certainly couldn't be your feelings, for they change so often, and that strange "I" never changes at all. All the time, that "I"

was not your body, nor your feelings, but the One who wondered, who did the thinking; the One you could not see nor hear nor touch.

We never think we are someone else, do we? Some people have received such injuries to their brain that they forgot even their names, where they lived, and all their family. And yet, they would ask, "Who am I?" and, when they got well, would make a new life for themselves, taking on a new name. The "I," the Real Self, was there, however much was forgotten, and with It, the power to create a new world for itself. Have you ever been so ill as to say, when you were asked a question, "I don't know. I can not think." The "I" must be somewhere even beyond the mind; It is, however little we think or know: That "I" can not be seen; It is the Seer. It has no color, shape nor size; It has no appearance so ever. But, it is the Real of us! It never changes. It is THAT without which would be no life, no beings anywhere, though It can not be seen nor touched. We can only say, "IT is, every where — always."

Socrates, who was a Wise One, once taught the little son of Hagnon in Athens, about the Soul. This is how he put it, as told in the book Gorgo: *

* By Charles Kelsey Gaines.

"Do you see the Long Walls?" he said. "They stretch far; but you saw that they had a beginning, and you know that they have an end. For all things that have a beginning have an end. Can you think otherwise?"

"But is there anything like that?" I cried.

"You know the meaning of what men call 'time'," he said. "Can you think that it had any beginning, or that it will ever have an end?"

"No; it goes on always. But time — it isn't anything at all," I persisted.

"Well," he said, "you, at least, are some thing; for you can think and know. But can you remember when first you began to be?"

"No; I cannot remember."

"Perhaps, then, there is something within you that had no beginning. And if that is so, it has had plenty of time to learn. Some think," he said, "that what we call learning is really only remembering. Already you have much to remember, little son of Hagnon."

"Yes," I cried, harking back, "and if it had no beginning it hasn't any end either; for you said so. My mother thought that; but she did not explain as you do."

"And if there is something within us that was not born and can never die, but is like time itself, can this be anything else than that

part of us which thinks and knows, which men call the soul?"

"It must be that," I said; "for they put the rest in the ground or burn it up. I never understood about the soul before."

"And now," said he, "which part do you think is best worth caring for, — that part which we cast away like a useless garment when it is torn by violence or grows old and worn, or that part which lives always?"

"It is foolish to ask me that; of course it is the part that doesn't die," I answered.

"I am glad," said he, "that you think this a foolish question. Yet there are many who do not understand even this; for just as some care only for clothes, some care only for their bodies. And that, perhaps, is why people do not remember all at once, but very slowly and not clearly, just as one would see things through a thick veil, such as the women some times wear before men. It is only when this veil, which is our flesh, is woven very light and fine, or when it has grown old and is worn very thin, that we can see anything through it plainly; and even then all that we see looks misty and does not seem real."

"Yes, but the women can peep over," I explained.

"And we, too, doubtless, can peep over sometimes," he answered, smiling. "It is better

then, as you think, and I certainly think so, to seek the things that are good for the soul, which is your very self, than to seek what seems good to the body, which we keep only for a little while."

"And that is why you wear no shoes!" I cried.

"What need have I of shoes?" he said.

Again I pondered. "What are the things that are good for the soul?" I asked him.

"There is but one thing that is good for the soul," he said. "Men call it virtue. But it is only doing what is right."

TO THINK ABOUT

- How many names are there for the First Truth of Theosophy? Can you find some names in the Lesson?

- How do you know that plants and stones are alive?

Can you answer this riddle?

What sends the bee to honeyed flower

Across the scentless desert ground?

What sends the condor miles to prey,

Though no man's eye the spot has found?- If you hurt some other person, either his body or his feelings, how many do you hurt? Why?

- "I am the origin of all. All things proceed from me." What does this mean?

- "I am not my body. I am not my feelings. I am not my mind." Please explain this.

MEMORY VERSE:

Never was I not,

Never was I not,

Never, never shall I cease to be.

Never the spirit was born,

The spirit shall cease to be never.

Never was time I was not,

End and beginning are dreams.

LESSON III

THE FIRST TRUTH — LIFE

MEMORY VERSE: "Life is not born nor dies. All is Life. Life is invisible, yet is in all things visible."

All is Life. We are Life. There is life in every atom, in every particle, however minute. Countless myriads of "lives" surround us all the time. Some are Fire-lives; some are Air-lives; some, Water-lives and some, Earth-lives.

It is Life and the lives that make all forms, whether the crust of the earth, the stone, the daisy, the elephant, or man. It is Life in all these forms that builds them and destroys them. Even the stone form will finally pass away, but the life once in that form will still be Life, in the soil or in the plant.

Our own bodies are made up of all kinds of "lives" — earth-lives in our bones, water-lives in — well, where are they? And we know that air-lives are in every part of our bodies; we breathe them in and out again. Besides, not only do we have heat, or fire, in our bodies, but how about the "sparks" that fly when we are enthusiastic, or when we are angry? All these "lives" are the same One

Life, but some have one part to do, and some another; some have the intelligence that be longs to the lungs, and others what belongs to the brain. But, isn't it strange that this body which seems so wonderful in what it can do doesn't know anything at all when We have gone from it? (That is, after what we call death.) It can't move at all, and the lives of all the organs stop working together. They begin to fight, and keep on fighting till the whole body is destroyed and gone. Even so, the "lives" are still Life. They can't get "out" of Life, any more than can the bird get out of the air in which it flies.

Now, if that is what happens to the body when We are out of it, isn't it worth our while to know what our work is with it, when We are in it? Can't we see, then, that we can no more live separate and apart from all our brothers, than the heart, or stomach, or breath in our bodies can say, "I am all; I am separate from all the other motions in the body."

What would become of our body, if the heart should say, "I don't care what becomes of the stomach." Then, suppose the stomach should say, "I don't care anything about the lungs; all I want is to be filled up and to get what I want." What would happen if the brain should say, "I have no use for the body. I am the whole thing in this body, and I will

just move on without being troubled with the rest of it that is always ailing and hindering my progress." Do you think the stomach would be able to do its work very long, trans forming the food into blood and bones and muscle? Do you think the heart would keep its rhythmic beat very long, driving the blood through the body? And how long would it take for such a brain to grow sick, itself?

We may call ourselves one small life or atom in the great Body of Life, and then it will be clear that when we injure any part of the same great Body, we do that injury to ourselves. Only, let us remember that it is what we do invisibly that harms the most; it is what we think and feel that helps or hinders. Have we ever noticed what happens when we are angry or selfish? when we take what belongs to another, of praise or of blame? when we try to get what we have not earned? when we are unjust to another? when we are unkind to others in our speech? Or, is it easier to see what happens when others are angry or selfish or unkind to us? We see what they do, yet do not realize they are mirrors to see ourselves by!

Theosophy is a mirror for inside seeing. But, we can not see it all at once. Inside seeing comes slowly. That is why Fables, too, make good mirrors for us. A Fable is a story in which we learn some truth about ourselves,

through the speaking together and acting together of animals, or plants, or any other forms of life. It is only Man, of course, who has speech, but we don't like to hear the plain truth about our foolish, harmful speech. We can listen and laugh or enjoy when animals are to be seen in the mirror, and perhaps, sometime, we see something of that animal in us I Listen, then, to the Fable of " LIFE".

Story "LIFE"

Once upon a time, the King of the Air, the King of Fire, the Earth King, and the Water King met together to decide which of themwas greatest, and most fit to be King of all the Nature world, and of man.

They had been quarrelling about it for a long while, and thought it was about time to settle the question; so they invited every thing in the world to come, and asked each one to say which King he thought should be the one great King of all.

It was like a wonderful party. Only it was very serious, because it was such an important thing, they thought, to decide.

The Wind and the Wave, and Sun and the Moon and the Stars were there; the Thunder and Lightning came together, the Mountains, and all the Four Seasons (who knows what

they are?) ; the Fruit Fairies and the Grain Fairies, and the Flower and Tree Sprites, the Fishes, the Birds, and Beasts, the Bees and Insects and Beetles, — oh, everything you can think of! (Who can think of something else?)

Yes, all were there except Man. He didn't seem to think it important to go. But Mother Nature was there, sitting on a very high seat where she could see all that went on. (Do you suppose that high seat was the sky?)

Of course, they had to have a judge, and everyone agreed that Life would make the best judge, to decide between the Kings; so when all were there, Life stepped before them so that all could see her.

She was dressed in the loveliest garment of shining colors you ever saw. It was so bright that it hurt their eyes to look at her, as it does yours when you look at the sun, you know. And so they all covered their eyes. But when Life saw this, she spoke to them so gently and kindly that it was like the sweetest music, and they all stood up and looked at her again. This time, the brightness didn't dazzle them but just seemed to fill them through and through with happiness and loving thoughts.

Then a wonderful thing happened. As they watched Life, her dress began to change color — from beautiful glowing red, to a shining orange, and then to yellow and into the loveliest

green like the sunlight on the grass; then into blue, and to a still darker blue, and then to violet, all the time shining and glowing with light, like beams from the Sun.

Well, as they watched those lovely dancing sunbeams shining from Life, what do you think? They saw, all of a sudden, that the same beams were shining through each one of them, too; and they were so surprised! You see, they always thought that each one has a little separate life all its own, different from everyone else's — when it was really only their bodies that were different. And now the Life Light was so bright that for the first time, they could see it shining through each one, and through Life itself, and it was all the same Life — no different in the rainbow than in the rose, no different in the beetle than in the bee, nor in the song of the birds nor the singing of the trees.

Now, this was all very wonderful, but, of course, each one could see only all the rest; he couldn't see himself yet. You know you can't see yourself unless you look in a mirror, and Life had not yet shown each one in her magic glass that the same life was shining through one as through all.

So each one thought, that though, of course, as he could see, all the rest had the same Life in them, he must be different himself!!! One

foolish little Bat flew out and told them he could see right through them all, but no one could see through him, — so he should be their ruler! He strutted and puffed, so that every one laughed loud and long at him. This wounded his vanity and the foolish little Bat collapsed completely and fell down on a heap of stones!

Suddenly something happened. The Kings began to think they weren't getting noticed enough. So each one, to show he was stronger, began to do terrible things! King Fire grew hotter, and hotter, and nearly burned every one up. The Wind blew so loudly and long, it tore up all the trees and rocks and made a dreadful noise. The Water fell in great rains and the Oceans spread over everything. The Earth shook down the hills and mountains. Then the Sun hid his face and everything grew cold, and froze, and it was all dark. And no Life could be seen anywhere. Oh, it was dreadful!

Now Mother Nature had been watching things, you remember, all this while, and she thought it was about time to interfere; so she came forward, and waved her hand, and commanded them to behave!

"How selfish you are!" she said. "Don't you see that by each trying to get the best for himself, everything is being spoiled, and no

one is getting anything? In a little while all your bodies would have been so destroyed that Life would have had no place to live, and would have had to go away from here. She is almost gone now, but perhaps I can call her back, for she can never die, you know."

So Mother Nature called and called, while they waited, ashamed and sorry for what they had done, and hoping it was not too late to try again. Suddenly the lovely light shone out once more, and Life stood before them more beautiful than ever! And her eyes were so bright and clear, that as they looked in them, they understood, at last, that there was the Magic Looking-glass, and so they saw them selves just as before they had seen all the rest; and they knew that it was the same Life — Light — Spirit — Self in every one — all in one, and one in all.

According as we think WE ARE, we do. And according as we think other beings are, we do to them. We perhaps now see that WE ARE LIFE. Now, let us read a companion story to "LIFE," in The Story of the Broom:

"THE LIVES"

In India, in ancient times, a little lad of twelve was taken by his parents to the college of the Wise Men, that he might learn to be

wise and holy, too, to help his fellow men. But the lad really would have preferred to stay with his brothers and sisters and friends, to play their games, to roam when he pleased in the fields, to swim when he chose in the river. The beautiful temple where Wise Men taught seemed lonely and cold to him; his lessons did not last all day, though they were interesting at the time, and his tasks for keeping order in the building where he lived grew daily more irksome.

Morning after morning Subba might have been seen sweeping out the Council-room with indolent strokes of the broom, — then resting in the open door, thinking of his playmates in the town who had only the task of amusing them selves. Hot resentment against this place of Wise Ones and the task would flame in his face, and as he walked up the path, he kicked the stones in impotent anger and, muttering, struck aside the branches of a shrub growing out a little over the path.

No one knows if that little lad ever became the Wise Man his parents hoped for — a Teacher for other little lads, willful and selfish as he was — but fifty years after his boyhood time, another lad with the same daily tasks came to his Teacher and said:

"My Teacher, it is my task to sweep out the Council-room each day, and this week I was

given a new besom. This besom is so different from the old one, I cannot make it sweep well. It is hard and stiff and when I have at last gathered up the dust in a little pile, suddenly the end of the besom will give a jerk and the dust be scattered again. May I not have my old besom back?"

"My Son," mildly replied the Teacher, "I think you can do better than that." Then he looked with intent eye at the refractory broom, and the picture of the lad of fifty years before came clear to his view. Turning kindly again to little Gargya, he said:

"The impatience and anger of a lazy boy is in that besom. Long ago he daily passed the way of the shrub that grew to make it, and to it, as he brushed it aside in anger, he passed on the angry atoms of his own body. You have learned how our bodies are changing all the time, throwing off old atoms and taking on new — and that other forms of life take on what we throw off, and give back to us again. It isn't so strange that this besom is unruly, you see, with so many atoms of it impressed by impatience and anger.

"But I said you can do better than cast it aside. Tell me, have you patience, son?"

"I try to do my tasks well, O Teacher, but now I see I might be more patient."

"Have patience then with this unruly be-

som, lad, and in three moon's time bring it to me again."

In three moon's time, the lad came to his Teacher with smiling face, the besom in his hand, and said:

"O Teacher, my besom has learned well. It is better now than the one I wanted back."

"Good, my Son," replied the Teacher. "It has learned well. And now I know you do have patience. Only a patient lad could have taught and changed that besom, wronged so long ago by impatience and anger."

TO THINK ABOUT

- Do we not judge if a thing is "alive" by its motions? If so, are we right? Can you explain the difference between the stone and human being?

- What kinds of lives are in the human being? How and where do these lives work?

- What is a Fable? What does the Fable "LIFE" teach us?

- If LIFE is everywhere, how can you say there is death?

- Which are most important, the inside or outside things?

- Can you describe the invisible Life? If our thoughts are invisible to others, is it possible for them to help or harm others?

Can you tell what this means, taught by the Buddha?

. . ."all things do well which serve the Power

And ill which hinder; nay, the worm does well

Obedient to its kind; the hawk does well

Which carries bleeding quarries to its young;

The dewdrop and the star shine sisterly

Globing together in the common work;

And man who lives to die, dies to live well

So if he guide his ways by blamelessness

And earnest will to hinder not, but help

All things both great and small which suffer life."(From The Light of Asia)

LESSON IV

THE FIRST TRUTH — SPACE

MEMORY VERSE: "Act for and as the Self."

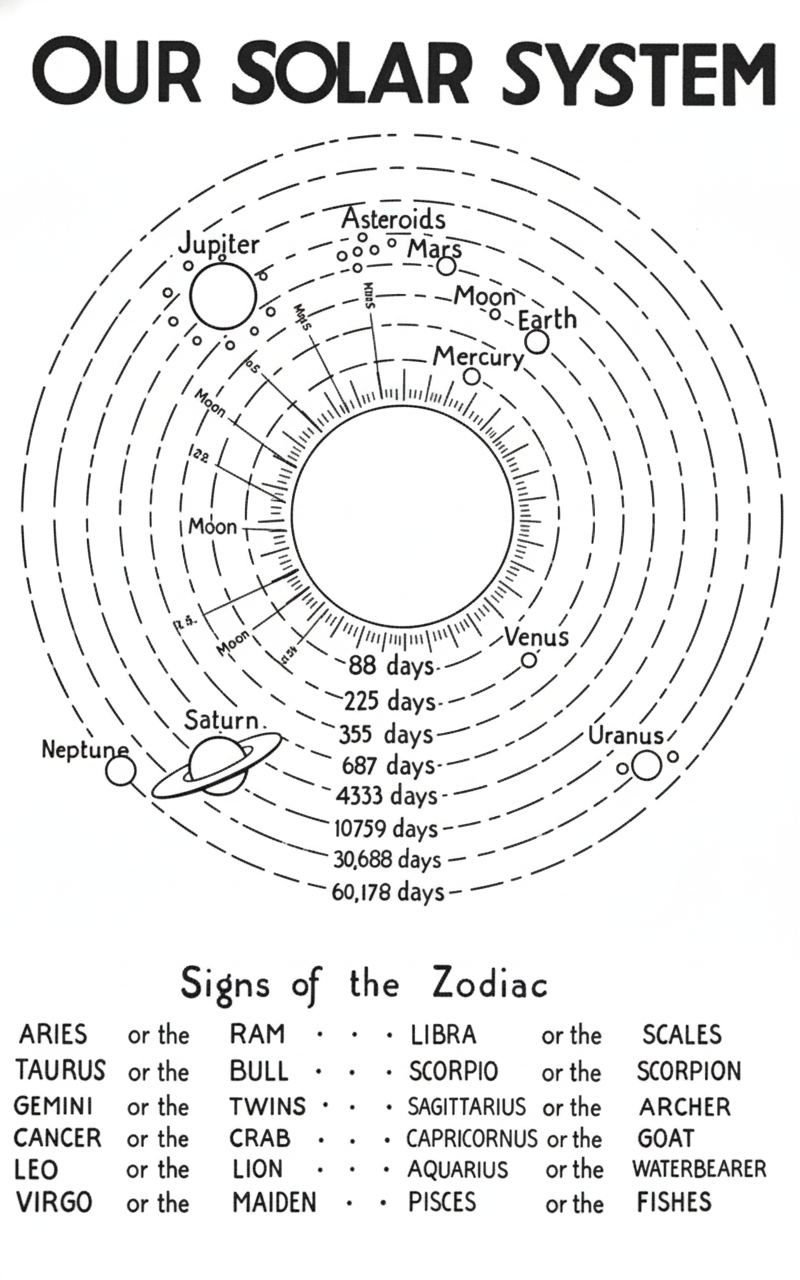

We don't see Life. We don't see space, because we look through it. Yet, can you think of anything that is not in space? The space where you are sitting now was there just the same before you sat down. It will be there when you get up. This building is in space, but, if it were suddenly burned down, the space would be there just the same. Supposing you had a powerful suction pump that would even take all the air out of the room? Still the space would be left! Supposing you found the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, you'd still be there, looking off into space. The sun is over ninety millions of miles away from us in space. Beyond that is still other space, so far that some of it can be measured only by light. So, the distance of stars is measured; but, beyond the farthest star, there is space beyond and beyond. You can't think where space begins and where it leaves off. Even when scientists measure the space of our solar system, they know there is space within and beyond other solar-systems. Everything is in space, and if there were no thing, nothing to be seen anywhere, still there would be Space.

Every being, however good and noble and wise, exists in space. So Space is greater than any being.

Can we not say all these things of Life? What can this mean, then, than that all Space is filled with Life? That there is no Space without Life? Now, you never would think of saying, would you, that Space is good, or that it is bad? You wouldn't say that Space is happy or unhappy? that it is cold or hot? But, We, who are beings — Life in bodies — can say we feel heat and cold; we can feel pleasure and pain. Pleasant summer breezes come out of space; fearful hurricanes, tornadoes and blizzards come out of space. In Space all things, both good and bad, are and live and act; but Space itself is neither good nor bad.

The Self, or Life, or Consciousness, is neither good nor bad. It is in all things; there is nothing without it; all things are in it. Can we see it? No. Just as we can see many things with our eyes, but we can not see our power to see; the Self sees all things, but can not see Itself. It is the Seer. Can we weigh it? Or measure it? Has it any color? Even in ourselves, can we see it or touch it? Each can only say, "I am." A Teacher once said to his disciple:

Put this salt in water, and come to me early in the morning.

And he did so, and the Master said to him:

That salt you put in the water last night — bring it to me! And looking for its appearance, he could not see it, as it was melted in the water.

Taste the top of it; said he. How is it? It is salt; said he.

Taste the middle of it; said he. How is it? It is salt; said he.

Taste the bottom of it; said he. How is it? It is salt; said he.

Take it away, then, and return to me.

And he did so. And the Master said to him:

Just so, dear, you do not see the Real in the world. Yet it is here all the same. And this soul is the Self of all that is, this is the Real, this the Self. *

Space is without color, weight, or size, and of it, we can only say, "It is." That in us not to be seen, nor touched, nor heard, is our very real Self. And the only way to know It is to act for, and as It, because we are that Self of all creatures. When we act for all beings, we act for THAT.

Our bodies are only instruments for the Self, or Consciousness, to look through — as we look through a microscope or through a tele-

* From the Upanishads

scope — in order to learn Great Truths about the Soul. Life makes bodies according to our needs. How may this be? Well, think of the fish that live in Mammoth Cave, without eyes.

When they are brought out into a stream, in the air and sunshine, after a time the new baby fish grow eyes to fit the new conditions! In Australia is the Ki-wi bird, which lost the wings it once used, because no longer is there need for flying from wild beasts into the tree-tops. Some say that nowadays people ride so much in automobiles that the next generation will cease to have the use of legs! But, certainly we know that if a great Flood should come upon the land, sweeping everything away but just ourselves, we should have to devise some other ways of getting lights than we have now! We are much more important than the lights, though, because we can make new kinds of lights, and new lights can not make themselves. We have Light within us — the Light of Self-Conscious ness — the Light of Soul.

The only way we really know anything is by being conscious of it. When you came into this room for the first time, the same things were in it as are now, but now you see many things which you did not notice before. They were there all the time, but you were not conscious that they were there. It is the Con-

sciousness in us which is the Knower, the Seer, the Chooser, the very Self. This is the Real, the unchanging Self, which sees and experiences all things in Nature — heat and cold, light and darkness. This Self sees the inside things, and knows if they are wise or foolish, pleasing or displeasing, good or bad. We ought never to make the excuse to ourselves that we do not know a good act from a bad one, because we do; we are conscious of which is right. And it is the choice of the right each time that makes our journey shorter to the Light of Truth, to Self-Knowledge.

What makes it so difficult for us to choose the right way? Always there are two things or ways to choose between — if not between wickedness and good, then between the better and the dearer. Life acts in two ways, everywhere and all the time. The ancient Krishna said:

"These two, Light and Darkness, are the world's eternal ways." (Memory Verse.)

We wouldn't know what light is, without darkness. Have we ever thought of that? Even plants know this. The great scientist, Darwin, once put two tender plantlets in a naturally lighted room. Then, he took one and put it in the very bright sunlight, the other in

a very dark room. The plantlet in the sun soon unfurled its baby leaves; but the one in the dark seemed to shrink its leaves and roll them closer. Then, he brought both back into the same room again. In a short time, both looked alike. But, changing them, now, the one that had been in the dark to the sunlight, and the one in sunlight to the dark, lo, the one put in darkness furled its leaves close and the other eagerly unfurled its tender leaves to the sun.

We wouldn't know what heat is without cold, nor what pleasure is, without unhappy times; what good is without bad. Light is the opposite of darkness; good is the opposite of bad; pleasure is the opposite of pain. (Who will name other opposites?) Who has noticed that sticks always have two ends? That every coin has two faces? Because we always have to choose between two things, between two ways, can we not see that the Path of which we talked in the beginning is the Path of our choices? We can act for and as the Self. Then, we are on the Path of Light. Or, we can act for My-self: that makes the path of darkness and sorrow.

Socrates again taught the little son of Hag-non, about right and wrong. *

* This and all other "Socrates" stories are from Gorgo.

WHAT IS "RIGHT"?

"Have you ever thought why it is," Socrates asked, "that some things are right and other things wrong?"

I had not, but I thought hard now. "It is right," I said, "when we do what the gods want us to."

"And if the gods should want us to do any thing that is wrong, or if they should do any thing wrong themselves — I do not say that they could — but would that make it right?"

"No!" I cried; for I thought bitterly of my mother, and how we had prayed for her in vain.

"Then right and wrong are something mightier than Jove himself."

"Yes," I answered. Again my spirit was humbled. "Tell me about it, Socrates."

"I will tell you, then, how it seems to me. To do right is to do what is truly wise. To do wrong is to make a mistake, — willfully, perhaps, but that is because we think that we are truly wise when we are not. The gods alone are truly wise in everything, and that is why only the gods make no mistakes and never do wrong. If I say anything that you do not think is so, you must stop me."

"Don't stop," I said.

"Well, then, could any real harm come to a soul that is truly wise, and always does what

is for the best and never makes mistakes — if that were possible? And it is possible, if we do not forget." He paused, but I did not speak. "And is not this the same as saying that nothing can ever harm the soul of one who does right and never does wrong, whatever may happen, now or hereafter? I do not think that we need to know just what it is that happens, little son of Hagnon."

"But there are such wicked men," I cried, "and if they catch you, it isn't any use to be good."

"To be wicked," he said, "is the greatest of all mistakes. It is as if a general should think that all his friends were enemies, and all his enemies friends. A man who is wicked, like the Syrian, is sure to do terrible harm to him self; but he cannot harm any other, not even a child, like you, unless he is able to make him also wicked. And that he cannot do unless you help him; for it is not wrong to suffer what we cannot help, and no such thing ever really harms us. No, little one, the wicked cannot hurt the good."

"But they do hurt them," I persisted.

"Let us be sure that we understand each other," he said. "I do not speak altogether of what most people call harm and talk about as good and evil, not stopping to remember, but of what is really so. I know that the Syrian

thought that he could harm us and meant to do it, and that you thought the same thing and feared him greatly; but you were both mistaken. In what way could he have hurt you?"

"He hurt my throat; and he might have killed me."

"If he had run a knife through your tunic, would that have hurt your body?"

"No, not if it was just the cloth that he cut."

"And even if he had cut the flesh and run a sharp knife right through the body, could he have hurt that part of you which is yourself, and does not die, and is only harmed by doing wrong? No, little one: it is very terrible to think about, but the worst that he could do, without your help, would be to tear or pluck away its garment from the soul."

"And that is why you were not afraid when the black man lifted up his knife?"

"That is why," he answered.

TO THINK ABOUT

- If it is true that Life always acts in one of two ways, how would you choose to use a knife? a match?

- What does "Act for and as the Self" mean? How can you act for the Self in the use of money, of books, of flowers, of candy, of clothes?

- How big is Space?

- Is the sun good or bad? Too much sun will blind a man, yet the sun causes the flowers to grow.

- Why can we not see the Self? Does It have a beginning, or ending?

- When plants and animals help each other, do they know it? For instance, some ants are fed by the juicy leaves of a certain plant, and these ants, in return, keep away other ants which would destroy the leaves. Other plants, without this juice to offer for food are eaten by the destructive ants. Do bees and butterflies, as they seek nectar for their food, know that they carry pollen from flower to flower and set the seed for another flowering?

- Who was Socrates? Why did he say that "to be wicked is the greatest of all mistakes"?

LESSON V

THE FIRST TRUTH — GOD

MEMORY VERSE:

"God can not be less than Space."

God is the highest in us. God is everywhere. God is Life, the Self, Spirit, Consciousness. Why is it, then, that we have kept this name — God — for the last lesson of the First Truth? Do we not know, now, that God can not be a being? Because any being' is in space, and so Space is greater than any being. And aren't We greater than any idea about space, because We have the idea? Consciousness and Space are not different. Why?

Our Inmost Self is the Real God, and all we can know of that God is in and of ourselves. Is it any wonder that Theosophy is called God-Knowledge? When we know that Knowledge, then, we are the highest beings in the universe. But, the highest beings are not God; they are gods, each one. So, we are a God within, but we do not know it, here on earth. Someone once said that we are Gods in the making!

Once, a little boy who had been taught by his mother that God is everywhere, cried out

to stop the car they were riding in. "Why?" she asked. And he said, "The car is riding over God, and I can't bear it. God is in the stones and dirt, isn't he?"

Where do you suppose he had gained the idea that Life, or God, could be hurt? Well, he had once been to Sunday School and had been taught that God is a being up in the sky, and not that God is within us and in every. thing. To him, God was a large Person. So, you remember that the ancient Greeks pictured the ocean as a Person — Poseidon. They pictured the heavens as a Person — Zeus. They pictured life in manifold forms as a Person — Proteus. And they pictured all Nature as the Person — Pan. But, what do you suppose Pan means? It means ALL — Everything. It was because in earliest times they knew Life to be in everything, each form of Life having its own kind of knowledge, or intelligence, that they felt more at one with all Nature. They knew they had all the powers that were in the sea and sky, in the mineral and vegetable and animal world. Their gods were the intelligent powers of Nature; but they also knew that all these powers came from the One Life, the One Power, the One Spirit. They did not make of THAT a person!

The gods and goddesses of ancient peoples

simply meant "the opposites." So, they had their Light-and-Darkness gods. But, in the course of time, these peoples lost sight of the Real, just as many Christian people have lost sight of the Real that Jesus taught, the God within. Christians have made of God a Good Person able to reward those who are good and make them happy. They have named God's "opposite," the Devil, or Satan, who has power to make people wicked; but, it is God who punishes the wickedness. All this is very con fusing, isn't it? Such ideas of "God" have been made by men. The Inner God is. So, we have to understand what is meant by anyone when he says, "God."

Many think "God" is a Spirit, who is every where outside themselves, so that they can "pray" to Him for what they want to receive, or to be relieved of; that He may do for them what they can not do for themselves. Suppose someone could do all our walking for us? Would we ever know how to walk ourselves? Suppose someone could do all our thinking for us? Suppose someone could do all our work for us? Can someone be happy for us, or can one be miserable for us? "Praying" in the real way, can we not see, is acting for and as the God within ourselves, not just now and then, but all the time.

HOW TO BE HAPPY

Helen was a little girl.

One morning she sat in the garden looking very sad, for Helen wanted to be happy, and she wasn't.

Along came Mr. Worm, creepy, creepy over the grass.

"Oh, Mr. Worm," said Helen, "are you happy?"

"Yes, indeed, my dear," answered Mr. Worm.

"I wish I were," sighed Helen, "will you teach me how to be?"

"Why, that's easy," said Mr. Worm, "just stick your nose into the ground, and wriggle like me, and you'll be happy."

So Helen stuck her nose into the ground, and wriggled like Mr. Worm. But she got her nose all muddy, and her dress all mussy; and she wasn't happy.

Very soon she saw Mr. Squirrel in a tree.

"0, Mr. Squirrel," said Helen, "are you happy?"

"Why, of course !" answered Mr. Squirrel.

"I wish I were," sighed Helen, "will you teach me how to be?"

"Certainly," said Mr. Squirrel. "There's nothing nicer than taking a flying leap from one tree to another. Just try it and you'll be happy."

So Helen tried it. But she scratched her hands and tore her dress, and when she tried to jump from one tree to another she fell down with a big bump; and she wasn't happy.

Just then she saw Mrs. Cat washing herself in the sun.

"0, Mrs. Cat," said Helen, "are you happy?"

"Always," answered Mrs. Cat, without stop ping.

"I wish I were," sighed Helen. "Will you teach me how to be?"

"It ought to make you happy to sit down here in the sun and wash yourself. You need it," answered Mrs. Cat.

So Helen sat down in the sun, which was most uncomfortably hot, and tried to wash herself with her tongue like Mrs. Cat. But it was not fun at all, and the mud on the end of her nose tasted horrid and gritty; and she wasn't happy.

So she walked way down to the end of the garden. And there under a rose-bush, sat The Nicest-of-All-Fairies. When she saw Helen she said:

"What's the matter, little girl? You don't look happy!"

"Oh, I'm not," answered Helen, "and I want to be — very much !"

"Very well, I'll tell you how. Only you must

do exactly as I say," answered The-Nicest-of-All-Fairies.

"I will, I will," cried Helen, "if only you'll make me happy."

"Then turn right around, and go back to the house. Go to your Mother's room and do what your heart tells you to do."

So Helen turned right around, and went back to the house and upstairs to her Mother's room. Mother was making a dress for Helen. The room was very hot and it wasn't at all fun to sew, but Mother wanted to get the dress finished for Helen to wear next Sunday. When Mother saw Helen she said:

"Why, Deane, are you tired of playing in the garden?"

And Helen's heart told her the answer.

"Yes, I'd much rather be up here helping you, Mother. Let me pull out bastings."

And what do you suppose? Before you could count, 1, 2, 3, and say Jack Robinson — Helen was Happy!

Do you know why, Dear?

— BRENDA PUTNAM.

TO THINK ABOUT

- Who, where, and what is God?

- Is there any reason why we cannot think of God as some kind of a being?

- If the ancients had the idea that Life is One, though each form of Life has its own intelligence, how could it be they lost this knowledge?

- What are "the opposites" taught by the Christians?

- What do the gods and goddesses of ancient people signify?

- Why is it important to know We are Gods in the making, rather than that some outside Power can make us good or bad?

- What is "the opposite" of knowledge? of selfishness? of courage? of truth? of right? of sleep? of generosity? of help?

COURAGE

Said the youth to the Sage: "O Father, I can not pass over that black chasm by this slender bridge! I shall fall in. I have not the strength to endure to the other side. I have scarce the strength to begin, heavily burdened as I am."

"Not your burden, but the weakness of your fear, is the weight," said the Sage. "You can not pass over thus weighted down. This bur den drop, and cross lightly to the other side."

But the youth's trembling held him fast to the brink of the abyss.

The Sage seeing, said: "Take the first step." The youth obeyed. And being on the swinging bridge, balancing the burden, he dared not turn about nor even look back, but went easily, swiftly over. When he was on the other side the Sage was there also.

Filled with the glory of accomplishment, the youth cried, "I did it! I did it!" Then remembering that he had left the Sage behind, he looked wonderingly at him in enquiry. "You came with me, Father?"

"Yes, I came with you all the way," said the Sage. "But, if you had faltered in doubt and fear on the brink, I could have done nothing. In taking the first step you let go the weight of fear, and the courage you assumed was augmented to carry you over."

"How simple it is, Father," said the youth, joyously. "I know I had not enough courage at the start to carry me over."

"You had enough to start, and by using it, you opened the door for all courage. Thus mine became yours also."

The youth looked at the Sage in the radiancy of gratitude, and then, as his gaze traveled back over the dark abyss, the light of his eye seemed to form one more thread in the golden strands of courage now spanning it — for other heroic souls to come.

LESSON VI

THE SECOND TRUTH — LAW

MEMORY VERSE:

"I am the origin of all. All things proceed from me."

Now, we have come to The Second Truth. Yet, this Memory Verse for it we became acquainted with when studying the First Truth. Do you remember that there is One Truth, but that It has three faces, or views? The Three Truths are simply three ways of looking at the One, and the other two Truths could not be without the First, any more than a plant could be without the seed. So, when we were talking about the First Truth, we found names for It, although we could not describe It, because It is the Changeless. We could only understand It a little better by looking at changing things, and beings, in motion. As soon as we did this, really, we were considering The Second Truth.

The Changeless of The First Truth is eternal, ceaseless Motion Itself. What we see is motions, not the Source of all motions. In the Changeless is the Power to change, the Power to act, the Power to think, the Power to build, the Power to destroy, and all Powers whatsoever. It is when these Powers

come into use, when beings begin to act, when manifold motions start in the universe that we can speak of The Second Truth, for this is the Truth which has to do with action — with beings, who and which act. This is a universe of action, and certainly we have thought enough about it to see that, by action, we mean much more than mere bodily action — the action, or motions of sun, and stars, and planets — because thinking is action; feeling is action; remembering is action; imagining is action — the action of our minds, rather than our bodies. Our minds, too, are always acting, always changing. But there is no action without Life and beings to make action — whether seen, or un seen.

We really live in two universes, don't we — the Unseen universe, and the visible universe? The visible universe "proceeds" from the Unseen Universe of Life, yet Life is in all things visible. Our visible universe is just a symbol of The Self.

So, the ancient Greeks pictured it as a great Egg, with the sky for its shell. Universe means the turning, or the motions, of the One Life — of all that can be seen anywhere in boundless space.

If we want to put The Second Truth into one small word, we can do so by naming it LAW. Whatever laws we may see or learn of,

in books and in great Nature, all proceed from the One Law — Life's eternal way of action. We are never going to find law in an important part of the universe, and no law in some forgotten corner of it! Why? Of course, if Life is everywhere, and the Power to act is every where, then Law is everywhere.

MEMORY VERSE: "This is a Universe of Law."

It is plain to see, then, that if we understand thoroughly any one thing in the universe, we shall know about all other things. Let us take an egg to study. Strange, isn't it, that every thing here on earth does come from an egg?

Isn't a seed an egg? The egg-shell is only a covering for a miniature universe of life. In the center of a hen's egg is a tiny point, or seed, or germ of Life, which is some day going to break the shell and come forth in a chick's body! That tiny point of Life stretches out on either side of itself, until it becomes a line from one side of the shell to the other. From that same point of Life also comes a line between the two long ends of the egg. Right in the egg, then, Life has made the form of a cross, in what look like lines of Light. That is why the Cross is a symbol of the Self acting in the body. Just notice, too, that when we hold our arms straight out from our bodies, we also make the

form of a cross. Could we not think of our earth, even, as a kind of egg? Then, we could see how the equator and the north and south poles came to be.

Well, you see, that line in the egg is the action of Life. Always, in every egg, that little point of Life stretches out into that line; it always acts that way, stretching out in two opposite directions, east, west — north, south. So we say, we "see" LAW at work. LAW is the name we give to Life's eternal way, or action. Seeing LAW in the egg, now you understand better, don't you, that "These two, light and darkness, are the world's eternal ways." These opposite ways of action must always be, wherever there is Spirit, Life, Consciousness. That is LAW. And from the way we see LAW work from the Life in the egg, we can understand how it is that LAW is within all things — not outside. The tiny point of Life in the egg is the cause of the line; the Self is the great Cause of all action. Without the point would be no line; without the Self would be no action anywhere — and so, no LAW. But the Self is everywhere, in all things. So wherever there is action, there is LAW.

The simplest things we do are according to LAW. We breathe in — and out. That is the only way we can breathe. That is LAW.

We walk, according to LAW, on the ground,

instead of in the air. Our bodies are made out of earth-stuffs, and so they are attracted to the earth. So our bodies pull toward the earth, and we pull them back at the surface, where we keep our equilibrium.

That is the way the earth stays in space, over ninety million miles from the sun. The sun attracts it just so far, and why it stays at that distance — balanced — in equilibrium, as we say, we shall see by studying a pair of magnets.

Each magnet has two opposite poles, positive and negative: if we put each positive against each negative, the two magnets cling together. If we put each positive opposite each positive the magnets push away, or are repelled. The sun is a great magnet; so when the earth gets a certain distance from the sun, it becomes magnetized like the sun, and therefore pulls away. All the planets of our solar-system have their motions regulated by the more powerful attraction of the sun. But it is the law in each body which acts with that in the other bodies. We, observing the action, always the same, say: That is LAW.

Just so, the tides of the ocean come in and go out again. The ocean is attracted by the moon and then the earth pulls it back again. But always the tide comes in for six hours; goes out for six ours. That is LAW. Never

by any chance does the tide come in for three hours, and go out for four.

It is LAW that holds the earth, and sun, and stars, trees, bodies of all kinds in their very shape. Do you remember that the stone which seems so hard is made up of tiny atoms whirling around a central point? Life — The Self — is the central point of all forms and beings. Once LAW should disappear from all these things, our Universe would be gone. Don't you remember how this nearly happened in the Fable?

A pair of scales teaches also the same lesson. In order to get the correct weight of some object, we have to put an equal weight on the other side. So we get the scales in balance, or equilibrium. This kind of balancing is going on all the time in this Universe. Every action causes the movement of "lives," whether to violence or harmony. This is LAW — and LAW means order.

It is such an orderly Universe, isn't it? Planets, stars, suns, moons — all stay in their exact places according to LAW. It looks as if we might think of our bodies as small universes, which we, the Self, must keep in order. When the motions of our heart and head and stomach and blood and nerves are kept in equilibrium, then we are strong. And isn't it sensible for us to keep all our possessions in order —

if order is in all things in the Universe? The more orderly we are, in body and in mind, surely the more we are acting for and as The Self; the better we render gentle service. And now we see that the laws men make to punish wrong-doers and keep order everywhere are just in imitation of the great LAW of the Universe. That LAW makes no mistakes.

TO THINK ABOUT

"The Universe is embodied Consciousness." What does this mean?

"Flower in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies,

I hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower — but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is." *- Would you also know what Law is?

- What and where is Law?

- Why do all cities and states and nations make laws?

- If a man who does not know how to swim goes into water beyond his depth and is drowned, is the water to blame?

- What is the meaning of the Cross?

- What would happen if the Law of the Universe should suddenly stop working?

* Tennyson.

SUSIE, THE CHOOSER

The nursery was a sight! Mrs. Newton's accustomed eyes surveyed a disheveled scene. Susie had been having a Theosophical School for a large and rather mixed family. The nursery floor was strewn with Teddy-bears of all sizes and ages, several rabbits likewise, a varied collection of dolls, some in the pink of perfection, some looking fearfully overworked and bearing indelible signs of ardent affection. I haven't time to tell you of all the things that lay on the floor, but it was very plain indeed that nothing had been picked up all day.

"Susie," called Mrs. Newton, "I want you to tidy your nursery before supper !"

Susie was having an exciting race on her tricycle with the little girl who lived across the street. The thought of going indoors and doing anything so uninteresting as putting away toys took all the joy out of the evening for Susie.

"Yes, Mother," she replied promptly. But she didn't go promptly! Oh no! she waited for just one more spin up and down, and one more spin up and down, until she was called in to supper before she knew where the time had gone to.

After supper while it was still light, they all went out to see a new rose that was in bloom. Susie lingered in the garden. The sky was still

in a sunset glow, the evening was very lovely, and Susie thought of her nursery with a shudder of dislike.

At last she went in. Someone had turned on the light, and it glared piteously on the wreck age. Susie could just reach the switch. She did so in haste, and, slamming the door, she dashed into the living-room, kissed Mummy and Dad "goodnight" in a hurry, and soon was in bed and not long after was asleep.

*****

The people moving around looked like shadows. The sky was gray and dead. Every one looked dull and sad. They groped in the gloomy dusk and spoke in hoarse voices from which the warmth of life seemed to have gone. Susie heard some of them saying that some thing had gone wrong with the sun. They did not know whether they would ever see it again; it had somehow gone out of its right track and had disappeared in the great unknown spaces of the sky.

(You know Susie was quite little, only six, and she thought the sun moved around the earth because it looks as if it does.)

Everyone was very sad as I have said, and some of the children began to cry and say that they wished the nice, warm sun would come back. Susie thought of the glory of the last sunset she had seen and she tried dreadfully

hard to swallow something that was sticking in her throat, and wiped away, very fast, some thing wet that was rolling down her cheeks, because she feared that never again would she see anything so beautiful.

Next thing she knew she was in her own be loved little garden, and what do you think? There were no pretty pansies, roses, Canter bury bells, nor any of her favorites to be seen, nor any that were not her favorites, for that matter. All the plants in the garden were growing with their roots sticking up in the air, and the flowers were buried in the earth. Susie picked up her spade and began to dig. She worked so hard, and dug such a deep hole, but the flowering end seemed to get farther away all the time.

Then the scene changed suddenly again, the way it does in dreams (for I know that you have guessed that this was a dream). Susie was standing down by the sea, watching the waves as she always loved to do. The sky was still black and there was a crowd of sad, anxious people hurrying to and fro. The great breakers crashed down on the sand as if they were angry with it and wanted to hurt it and then swept up, up, up the shore, spreading white foam along the beach as far as the eye could see. Higher and higher swept the waves. Men hurried around with sand in sacks. Then at last a

man who held a watch in his hand cried out in a loud, frightened voice:

"The tide has not turned! The tide has not turned! It has been coming in for long beyond the right time. This has never happened in the world before! We shall all be drowned! Make haste. Run for your lives!"

All turned and ran far inland, but the sea kept coming in and pounding just behind them. Susie heard some one say:

"It seems as if there is no law and order in the Universe !"

She was so tired! And at last, when she felt as if she could not take another step, and would have to let the waves overtake her, she opened her eyes and found herself all under the covers of her own little bed.

She lay and looked out of the window at a large bright star in the heaven, and she thought:

"Oh, how glad I am that there is law and order in the Universe! I wish I had tidied my nursery last night. That was a moment of choice, when I turned out the nursery light and left my toys, and I chose the crooked path. I will straighten it up first thing in the morning."

She did too.

Sometime I will tell you more about Susie.

LESSON VII

THE SECOND TRUTH — KARMA

MEMORY VERSE:

"Thoughts are the seeds of Karma."

We can't see Law any more than we can see The Self. We can see only action and motions, and when we see things happen in just the same way, with fire, or water or air or earth, for instance, we say this is the law of those elements. We know now that this is a Universe of Law — that the sun, moon, stars, earth, ocean, and the small earths we call our bodies, all are obeying Law — the Law within them — and so keeping order. They don't know they are obeying, but they do obey; they cannot act in any other way than as they do act. But we can act as we choose; we are the Thinkers and the Choosers, who can obey or disobey the Law, though still the Law goes on, whether we show obedience or disobedience to it. Just as the Self is the cause of the Universe and its Law, or way of action, so we, the Thinkers, are the cause of all that comes to us in our bodies. Everyone agrees to call that, Law, which holds the universe in its place, but there most people think Law stops. Only the wise men of old, and only Theosophy,